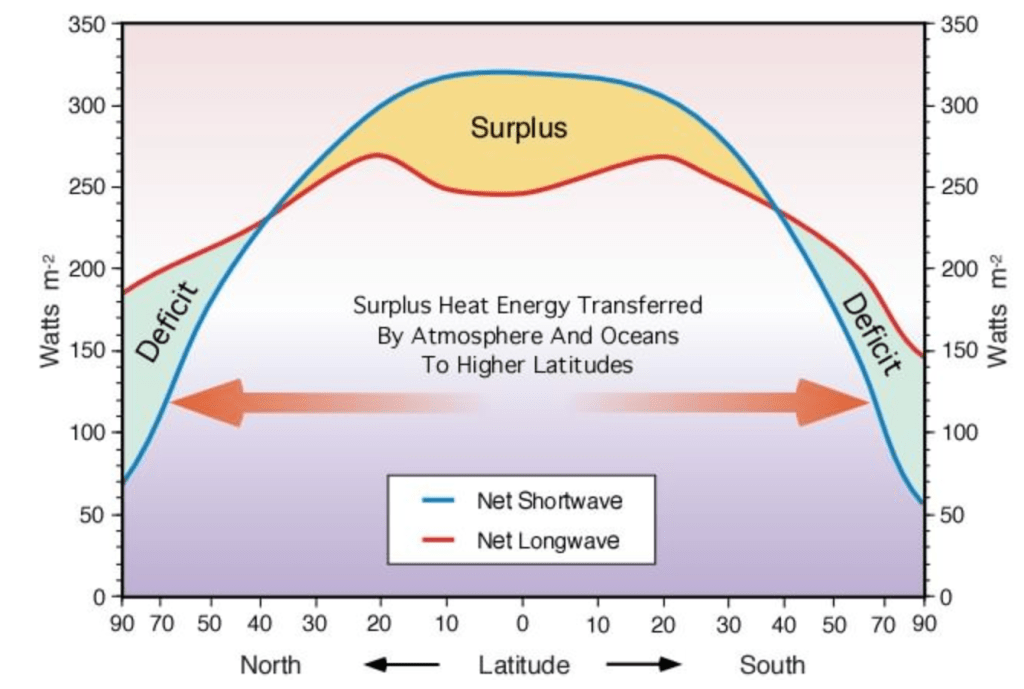

The role of the Atmosphere and Ocean in Exporting Heat (and Moisture): Just as an Earth with no atmosphere would be colder and would have starker temperature differences between day and night than is observed, an Earth with no atmosphere would also have sharper contrasts in temperature depending on latitude and season than is observed. The atmosphere (and ocean) act to redistribute heat from tropical regions to polar regions.

http://www.physicalgeography.net/fundamentals/7j.html

Because of these processes and because of the ice-albedo feedback, as the Earth warms, it does so disproportionately rapidly at the poles – particularly in the North Polar region. The air mass over Antarctica is somewhat more dynamically and functionally isolated from the rest of the world by both very strong oceanic currents in the Southern Ocean and a very strong jet stream in the atmosphere. These processes have limited the flux of lower latitude heat to the continent of Antarctica. But this may be breaking down. High northern latitudes have been observed to warm at 3-5 times the rate of the global average (cite).

Similarly, much more water is evaporated at low latitudes than at high latitudes and the global atmosphere acts on balance to transport moisture from lower latitudes to higher latitudes (especially in the middle to high latitudes – the picture in the tropics is complicated by processes of global atmospheric circulation).

Marine/continental interior and the role of prevailing winds: Because of the high heat capacity of water (amount of thermal energy required to change the temperature of a body of water), climate change is also more rapid in continental interiors, far away from the moderating effects of oceans. Over the ocean and near the ocean, much of the excess heat is absorbed by the ocean – muting its effect on the surface temperature.

The direction of the prevailing winds also play an important role in this – particularly in the mid latitudes: the coastline facing the prevailing winds (western coast of North America and Europe in the Northern Hemisphere and western coast of South America) tends to have a milder climate (less extreme summers and less extreme winters) than the east facing coastlines of the Americas or Asia at the same latitude. In the low latitudes, since the annual temperature contrast is relatively limited, this effect is more limited. In the very high northern latitudes, the Arctic Ocean experiences a smaller temperature range than the surrounding landmasses, but most areas near the Arctic Ocean experience onshore winds. In the Antarctic, the prevailing winds blow from the center of Antarctica outward to the coast, so there is little moderation of temperature for much of the Antarctic coastline except areas like the Antarctic peninsula.

September of 2023 was the most anomalously warm month in recorded history with a global mean anomaly of almost +1.5C. The global anomaly map of September 2023 (relative to the 1991-2020 baseline) is shown below and clearly exhibits the amplification of warming at the poles and in continental interiors. The very warm anomaly in the East Pacific is a sign of a robust El Nino signal and the pronounced warming in Antarctica is a worrying sign.

Source: NOAA NCEI Gridded Historical Climate Network (GHCN)

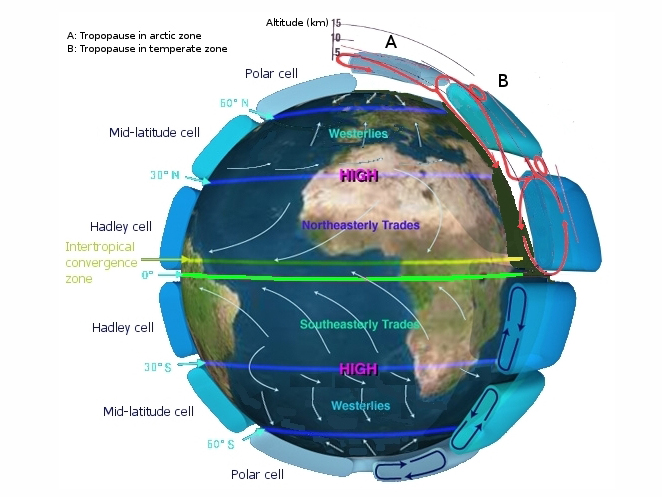

Hadley circulation, Ferrell Circulation and ecosystems: The figure below shows the very rough, approximate diagram of wind patterns in the two hemispheres. On balance, the atmosphere works to move heat from low-latitudes to high latitudes. But this picture is complicated by three distinct atmospheric “cells” in each hemisphere in the low, middle and high latitudes respectively. These features arise from the physics of a rotating planet. While the real Earth has a more complex boundary between these cells than is depicted below (the boundaries shift seasonally are not located at exactly 30 and 60 degrees from the equator), the diagram below is a rough heuristic approximation.

source: http://sealevel.jpl.nasa.gov/overview/climate-climatic.html

In each hemisphere, the tropical or Hadley cell is dominated by easterly winds (winds blowing from east to west) at the surface moving towards the equator (or more precisely, the ITCZ). The converging air rises along the ITCZ, cools, releases rainfall and the return flow aloft moves towards the subtropics where it subsides, causing deserts.

In each hemisphere, the mid-latitude cells are dominated by westerly winds at the surface moving from low latitudes to high latitudes. This air converges with the polar front around 60 degrees away from the equator, although the positioning and strength of this convergence is dependent on the season, the jet stream and other prevailing geographical characteristics.

In the polar zones of each hemisphere, from 60 degrees to the poles, sinking/subsiding air at the poles flows equatorward and in an easterly direction to the polar front.

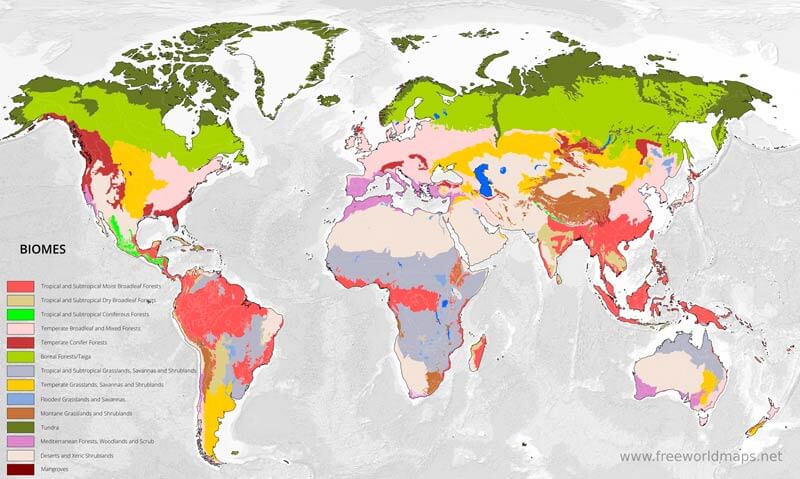

These large scale features of the atmospheric circulation have a significant impact on the geographic distribution of biomes and ecosystems throughout the world – as shown below. Most of the major deserts of the world are either in polar regions or at or near the subtropics. All the tropical rainforests and seasonal forests are in the very low latitudes. The middle to high latitudes tend to be dominated by a mix of forest and grassland landscapes depending on proximity to water and prevailing wind direction.

source: https://www.freeworldmaps.net/biomes/

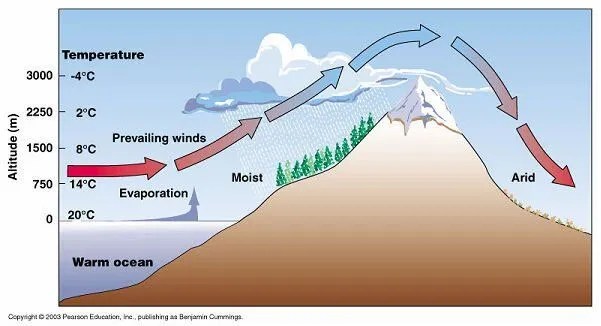

High elevation/versus low elevation: Throughout the world, in the troposphere (lowest layer of the atmosphere), the lapse rate is negative – meaning that the temperature tends to decrease with increasing elevation. Just as the atmosphere tends to export heat from warm regions to cold regions laterally (low latitudes to high latitudes), the atmosphere also tends to export heat from warm regions to cold regions vertically and in a warmer world, atmospheric isotherms (lines of equal temperature) tend to move upwards. This phenomena has been observed in many mountain ecosystems and has been accompanied by a rapid and wide-scale retreat of many mountain glaciers (Rutgers study).

Windward side/leeward side: In addition to the bulk influence of elevation on rainfall and temperature, the direction of the slope of a mountain relative to the wind plays an important role in local climate. Generally, slopes facing the prevailing wind or “windward side” tends to receive more precipitation because the air passing over that slope is rising, cooling and tending to induce precipitation. Slopes facing away from the prevailing wind “leeward side” tend to receive little precipitation, because the air is descending, warming and therefore not leading to much precipitation. These combined effects of elevation and slope on precipitation and temperature are shown in the figure below.

source: https://www.dtn.com/how-do-mountains-affect-precipitation/

Surface vegetation/climate feedbacks: Plants store water and the larger and more complex the plant, the more water it can store. Plants release water vapor to their immediate surroundings through a process known as transpiration. It’s estimated that in some environments (like the Amazon rainforest) transpired water from the trees accounts for almost half of the water source for the annual rainfall in the region. If many plants die off, that valuable water resource dwindles and the local atmosphere is denied a valuable water source – which can lead to a vicious self-amplifying cycle. However, the converse is also true – reforestation or the intentional planting of new shrubs or forests in otherwise more denuded or sparse landscapes can help the ecosystem in many ways – by sequestering more carbon, improving biodiversity, nourishing soil and by providing more moisture for the region’s local climatology.

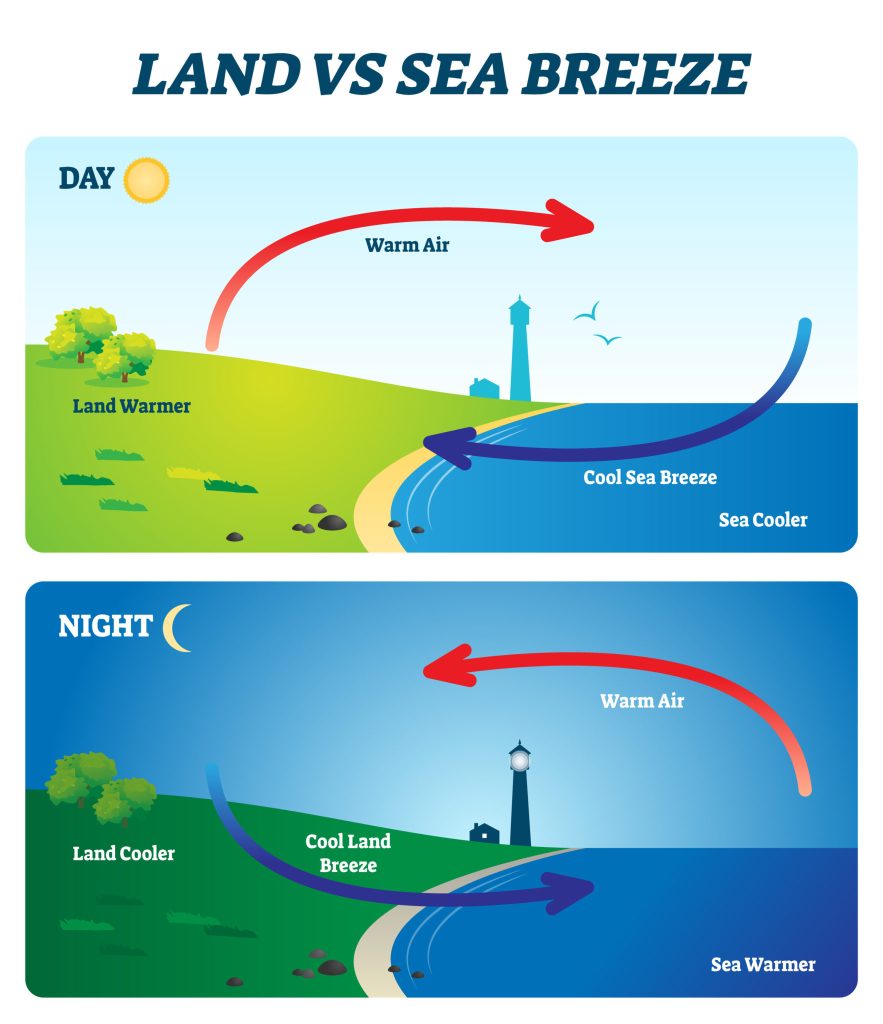

Sea Breeze/Land Breeze and Monsoons: Because water has a higher heat capacity than air, the land typically heats up faster during the day than does the ocean and the land typically heats up to warmer temperatures in the summer than does the ocean. Conversely, the land typically cools down to lower temperatures during the night and during the winters. This is depicted in the image below. The hotter temperatures over the land during the day drive onshore winds from the ocean during the day – whereas the warmer temperatures over the ocean at night drive offshore winds from the land to the ocean.

The dominant driving force behind seasonal rainfall in the tropics are the “monsoons” which can typically be thought of as land-sea breezes on a continent or subcontinent geographic scale and on a months long time scale. When the land heats relative to the ocean, onshore flow is initiated and typically, rainfall will intensify. When the ocean is warmer than the land, the atmospheric flow is offshore and the conditions are drier.