In the climate system, there are a number of sources of uncertainty and there are many processes that are not yet resolved well by climate models. This lack of certainty is part of any scientific enterprise of similar complexity (there are similar uncertainties in other complex branches of science – quantum computing, neuroscience, many branches of biomedical science, etc.). Scientists have an intellectual responsibility to communicate uncertainty, but the implications of this uncertainty is often misperceived by the public and is used to foster “climate skepticism”.

The uncertainty and lack of definite knowledge of how certain climate processes work emphatically does not mean that a) climate scientists are charlatans, b) anthropogenic climate change is a hoax or that c) the best scenario of the range of uncertainty will be realized. Many climate scientists are very smart, hard-working, honest people trying to better understand the processes that govern the workings of this planet and share their knowledge and discoveries with the public. While there are uncertainties about certain processes, this does not obviate what we do know about the connection between greenhouse gases and warming. And the level of uncertainty should, if anything, be a cause for greater concern, rather than greater complacency – because the uncertainty means that things might actually be worse than we thought – for example with sea level rise.

Some of the uncertainty comes from challenges with measurement and model resolution. Some of the uncertainty comes from complex feedback mechanisms that are not fully understood. These feedback mechanisms in the coupled ocean-atmosphere-land system may be self-amplifying (positive), self-damping (negative) or a bit of both depending on the context.

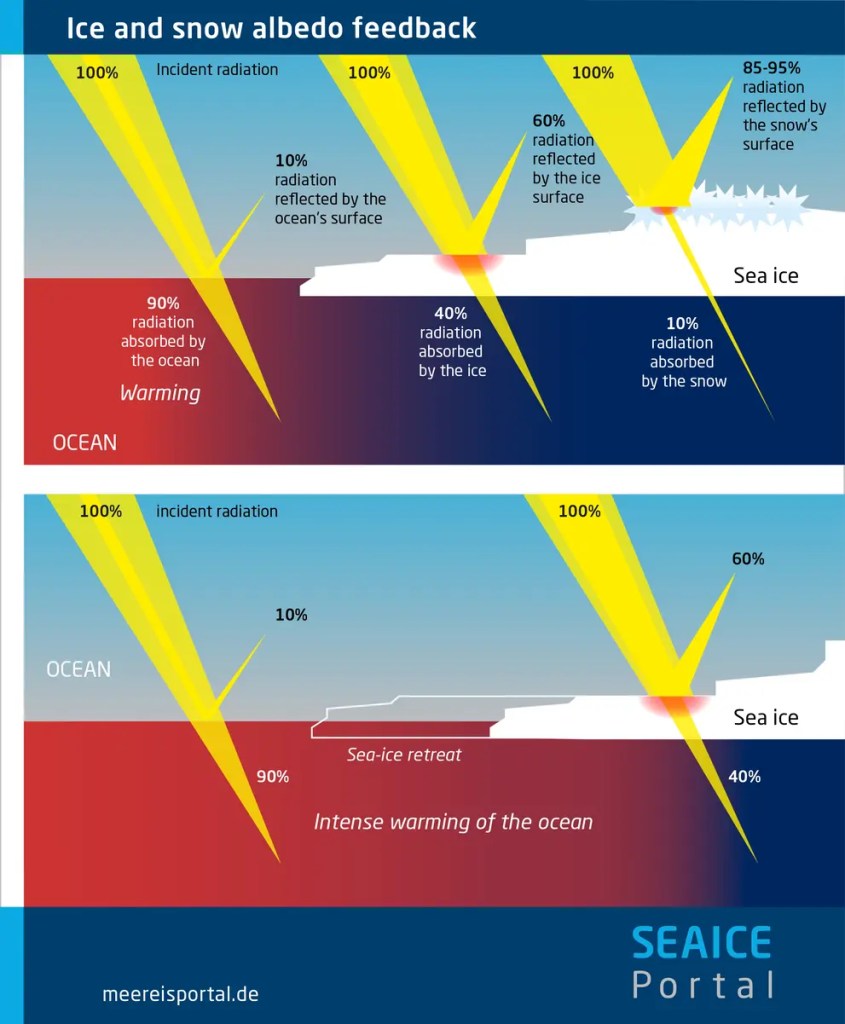

Ice-Albedo: The clearest example of a positive feedback mechanism which tends to “self-amplify” is the ice-albedo feedback. Simply put, snow and ice are highly reflective surfaces and the land or ocean that is exposed when snow and ice melt away are much darker and more absorbent of solar radiation. Therefore, the more snow and ice that melts, the more dark surfaces are exposed, the more the Earth’s overall reflectivity to incoming solar radiation decreases and the more the overall temperature of the Earth increases…which leads to more melting of more snow and ice. A slight variant of the ice albedo effect is that when snow and ice surfaces are darkened by accumulation of soot or other dark particles or material, this has a similar effect of enhancing the rate of melt. This ice-albedo effect is largely responsible for the significantly higher temperature increases observed in the polar regions than the global average and that trend is confidently expected to continue, although there are some uncertainties regarding the exact rate of this feedback mechanism. The schematic diagram below illustrates this process particularly with respect to sea ice cover.

source: https://www.meereisportal.de/en/learn-more/sea-ice-physics/sea-ice-and-energy-budget

Glacier Ice Dynamics: There are substantial uncertainties regarding the dynamics of melting glaciers in the world’s polar regions. If the only process at play involved melting ice from the surface of the ice sheet and the meltwater running over the surface of the ice sheet to the ocean, we could breathe a bit of a sigh of relief, because the rate of melt of glaciers and ice caps would be relatively slow and we could be confident in the idea that it will take a long time to melt enough of the ice caps to significantly raise global sea level – thereby giving us a bit more time to adapt.

However, plenty of recent research and observation indicates that this is not the case. There are two other processes at play that tend to lead to more rapid melting: oceanic warming of outlet glaciers and basal lubrication.

In both Greenland and Antarctica, much of the bedrock geology beneath the ice sheet consists of relatively high terrain with ring of mountains near the coast. This works to the world’s advantage as that topography inhibits the flow of these ice caps into the ocean. But on both ice sheets, there are gaps in these mountains and areas where there are marine-terminating “outlet” glaciers that directly interact with the ocean surface. The majority of the ice lost to the sea happens in these areas. But there is some evidence that increasing the sea surface temperature just slightly in these areas can dramatically increase the rate of glacial calving and flow into the ocean. This is a particular concern in the West Antarctic Ice Sheet where much of the bedrock underlying the ice is below sea level and there are larger sections of the ice sheet that may be exposed to warming ocean water.

Another source of concern is that on both Greenland and Antarctica, during melting periods, large pools of meltwater form on the surface and sometimes find weaknesses in the structure of the glacier and tunnel their way down to great depths, sometimes even all the way to the bedrock. These features are called “moulins”. When meltwater finds its way to great depth in the ice sheet or to the bedrock/ice interface, the frictional forces that keep the ice sheet relatively slow moving are reduced and there is a greater potential for more rapid movement and destabilization. The images below show a moulin on the surface of the Greenland ice sheet and a marine terminating glacier in rapid retreat from a study conducted in 2022.

source: https://news.ucsc.edu/2022/02/melting-glaciers.html

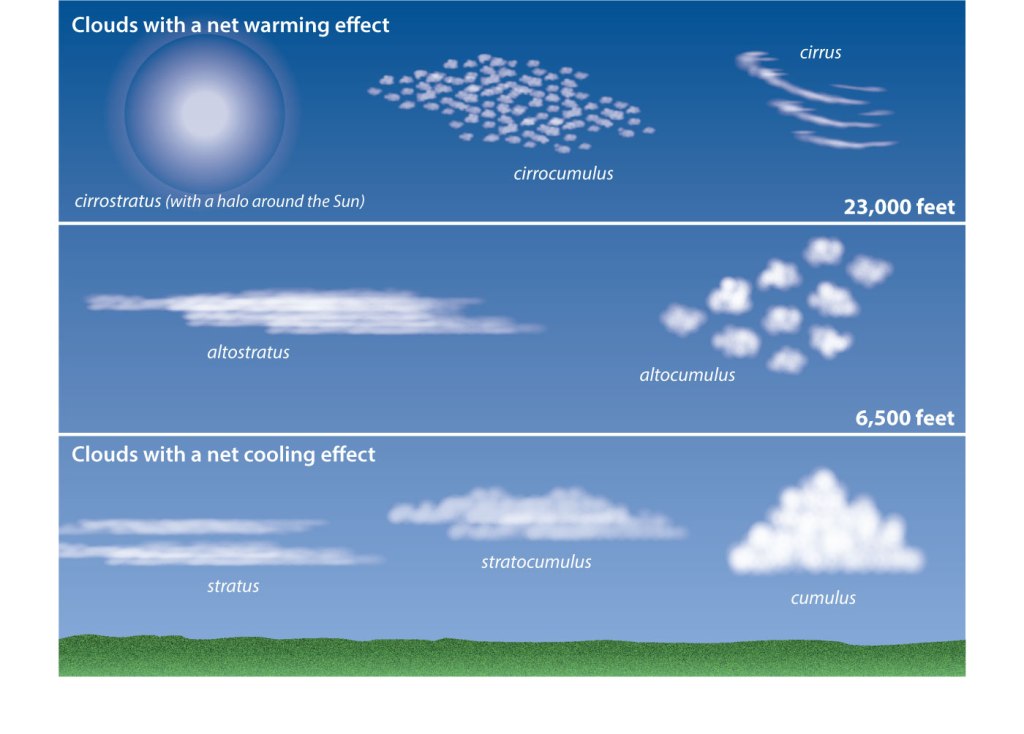

Cloud-Water Vapor: As has been mentioned elsewhere on this site, a warmer atmosphere will hold more water vapor, which is, itself a greenhouse gas. That direct radiative component of this feedback is positive – but the story is more complex. More water vapor in the atmosphere and more precipitation also tends to imply greater latent heat release to the atmosphere, which may partly counteract the warming from the GHG potential of the water vapor. Furthermore, there is the issue of clouds: some types of clouds tend to absorb more radiation from the surface than what they reflect in the way of incoming solar radiation, thereby representing a net warming effect – this tends to include both cumuloform and cirrus clouds. Other types of clouds (stratus clouds – particularly low in the atmosphere) tend to reflect more sunlight than what they absorb from surface radiation, representing a net cooling effect. It is not really known which process will dominate as the climate changes. This is described further below.

source: UCAR Center for Science Education

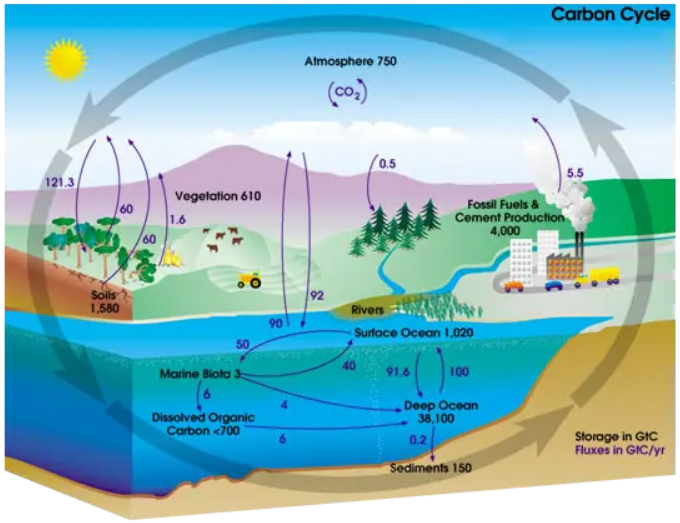

Biology and Land Surface: The world’s forests, soils and oceanic phytoplankton play a vital role in the carbon balance and the land surface also plays an important role in the radiative balance of the planet. A little less than half of the emitted carbon from human activity goes into the atmosphere, with most of the rest being absorbed by plants and phytoplankton. Clearly, human-caused environmental degradation like deforestation change that balance in the direction of reducing the capacity of biology to absorb CO2.

source: https://earthhow.com/carbon-cycle/

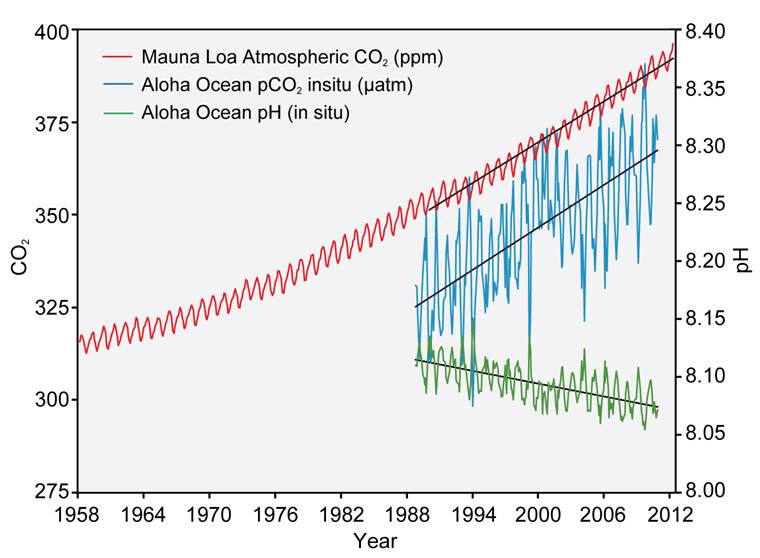

Ocean Carbon: A considerable amount of excess carbon (around a quarter of what humans emit) is absorbed by the oceans. Phytoplankton and other larger marine plants (kelp, seaweed, shallow water sea grasses, etc.) are the primary biological vehicle for this carbon sequestration. But a significant flux of carbon into the ocean occurs chemically as a product of concentration imbalances between the atmosphere and ocean. Some of the carbon that is sequestered into the ocean remains in the surface ocean where it can be easily exchanged back to the atmosphere depending on biogeochemical and physical processes. Some of the carbon that is sequestered is brought deep into the ocean – beneath the thermocline, where it is entrained in deeper water and may stay for centuries.

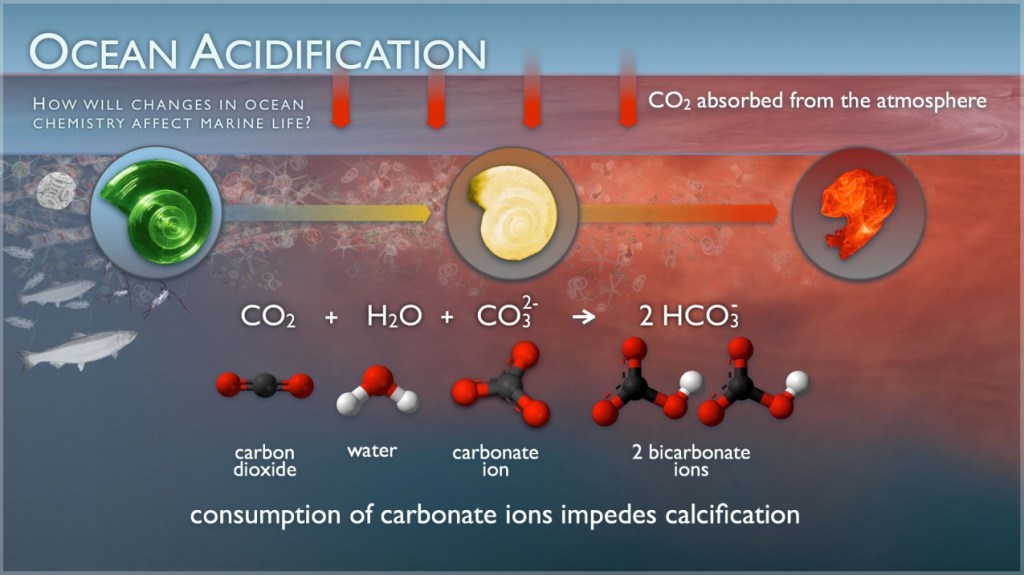

As the planet warms, the surface ocean becomes warmer, which decreases the absorptive capacity of the surface ocean. As the planet warms, Furthermore, much of the excess carbon that winds up in the ocean forms carbonic acid – which has the effect of acidifying (lowering the pH) of the ocean. This combination of warming temperatures and acidifying chemistry has already had a devastating impact on many marine ecosystems – especially including coral reefs – which have experienced mass bleaching events in recent years. The schematic diagrams below illustrate the overall ocean-carbon balance and the process of ocean acidification.

source: https://www.iaea.org/topics/oceans-and-climate-change/the-ocean-carbon-cycle

source: https://www.noaa.gov/education/resource-collections/ocean-coasts/ocean-acidification

source: modified from Feely et al. 2009

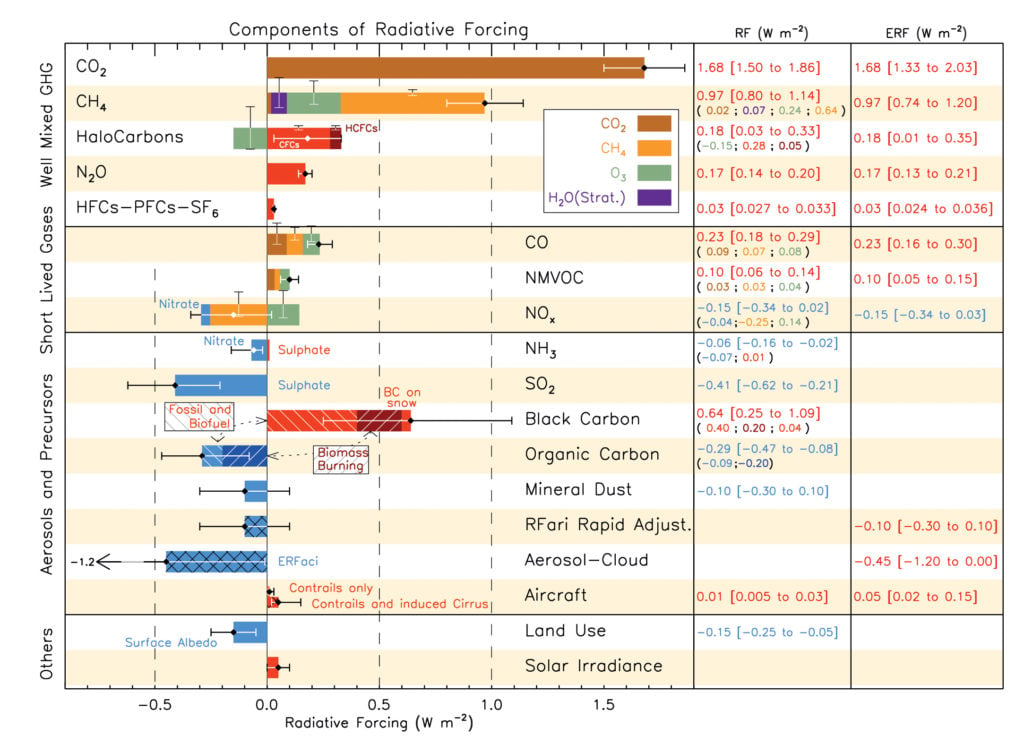

Aerosols: In the atmosphere, there are a wide range of aerosols – some are particulate solids, while others are liquid. Some have a natural cause, others a manmade origin and some have sources from both human and natural causes. The effect of aerosols on the radiative balance of the Earth and consequently, the temperature is highly specific to the individual type of aerosols. Some effects are direct (meaning the aerosol itself absorbs or reflects radiation). Some effects are indirect (the aerosol chemically reacts with something else in the environment to produce a radiative effect).

In sum total, aerosols tend to have a net cooling effect. But again, the effect of aerosols is very specific to each different type. Sulfate aerosols have historically been responsible for the most cooling, whereas black carbon has historically been responsible for the most pronounced warming.

source: IPCC AR6 (2021 – Working Group 1)

Thermohaline circulation: While the motions of the upper layer of the ocean are driven primarily by the force of the wind, friction with continental boundaries and coastal margins and the rotational forces of the Earth, there is also an exchange of water masses from the surface ocean to the deep and vice versa. This exchange of water masses is known as the “thermohaline circulation” and the Atlantic component is termed the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC). The primary driver of this exchange is the rate of water sinking in specific “deep water formation areas” where surface ocean water gets dense enough because of environmental factors that it sinks down hundreds or thousands of meters. Throughout the rest of the world ocean outside of these deep water formation regions, there is a gradual, persistent upwelling to achieve global net mass flux balance. There are also specific regions where the upwelling rate is faster and is dynamically driven by surface winds – like at the equator and along the eastern margins of the ocean basins.

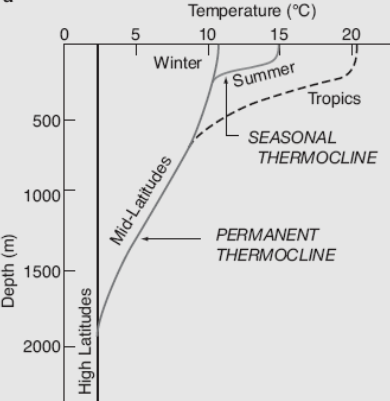

For much of the world ocean, in low to mid-latitudes during non-winter months, there is an effective separation between surface waters and deep waters (below a few hundred meters) because of the effect of temperature on density. Waters near the surface are warmed by the Sun. Warmer water is lighter/less dense and stays near the surface. Because sunlight attenuates with depth, deeper waters do not experience the warming effect of the Sun’s rays and tend to remain dark, cold and dense. The transition zone between these two water masses (the deep and the surface “mixed” layer) is called a “thermocline” and also leads to a zone of density transition or “pycnocline”. A diagram of this concept is shown below.

However, in addition to temperature contrasts leading to density differences, differences in salinity also lead to differences in density, with fresher water being lighter/less dense than more saline water at the same temperature. Warm fresh water will always float above comparatively cold and salty water, but the picture gets more complex when considering one mass of water that is relatively warm and salty and another that is relatively cold and fresh.

There are coefficients in the ocean’s equation of state that describe the relationship between temperature and salinity differences and respective changes in water density. These coefficients are not constant with respect to temperature or salinity. But basically, if the temperature effects dominate, the system is said to be “thermally controlled” and if the salinity effects dominate, the system is said to be salinity controlled”. Throughout the Holocene (last 20,000 years), the world has been in a “thermally controlled” system of thermohaline circulation with deep water formation regions in the coldest parts of the world’s oceans in the Arctic/North Atlantic and in the Southern Ocean around Antarctica. This is depicted in the diagram below.

source: https://www.pik-potsdam.de/~stefan/thc_fact_sheet.html

While not shown in the diagram above, there is also some (limited) salinity driven formation of “intermediate water” in the Mediterranean basin. Relatively fresh water flows into the Mediterranean basin near the surface at the Strait of Gibraltar, experiences net evaporation and increase of salinity in the Mediterranean because of the arid climate, and sinks to the bottom of the basin, where it flows back out the Strait of Gibraltar at greater depth and then sinks to a depth of about 1000 meters in the Atlantic.

This global process is also sometimes termed the “global ocean conveyor belt” – a phrase popularized by the late geochemist and oceanographer Wallace Broecker. This has been an important, but controversial idea. While the current arrows shown in diagrams such as this have research behind them, the reality of ocean currents is much more complex than can be easily captured in such a diagram. While scientists have estimated that on balance, molecules of water in the ocean have an average “residence time” of about 1500 years if they get entrained into the deep circulation, not every molecule of water follows the path described in the diagram above and many spend considerably longer (or shorter) in the ocean than 1500 years before being exchanged with the atmosphere or groundwater. The idea that this pattern of currents is a “conveyor belt” is also a bit complex because it implies that changes to the rate of sinking and rising motion must have a direct impact on the aggregate speed of the surface currents – despite the surface horizontal currents being much faster and driven by different mechanisms. While it is a physical truth that mass flux balance must be conserved, there is not necessarily a direct one to one relationship between a slowdown (or speed up) of the vertical fluxes and the horizontal fluxes and it is readily possible for an ocean to have mass flux conservation and have either more or less vertical exchange.

By warming the planet as much as we are, we are unequivocally, causing the polar ice caps (Greenland, Antarctica and many smaller ice bodies in polar environments) to melt and flood the high latitude oceans with relatively cold, but relatively fresh water. This fresher water is less dense/more buoyant than was typical before the Industrial Revolution, so the rate of sinking is slowing down. This does have important consequences for the climate system in its own right. The deep ocean acts as a carbon sink and carbon entrained in the deep ocean doesn’t interact much with the atmosphere. When the rate of sinking decreases, the rate of deep ocean carbon sequestration declines and more of the oceanic carbon stays near the surface where it can be exchanged with the atmosphere, leading to further increases in GHGs and further warming. Furthermore, deep water formation is the primary mechanism for bringing oxygen rich water to great depth…so when the deep water formation rates decline, over long time scales, the deep ocean will become depleted in oxygen. Furthermore, if the surface ocean becomes warmer, there may be additional thermally induced sea level rise. One recent study in Nature has shown an alarming observed decline of deep water formation in one of the seas around Antarctica on the order of 30% in the last 30 years. Here’s another related Nature article.

There is an apparent connection between the slowdown of the AMOC and strong surface currents, like the Gulf Stream and Kuroshio currents. A recent paper in Geophysical Research Letters shows that over the last 40 years, there has been a 4% reduction in the speed of the Gulf Stream off the east coast of Florida. However, it should be noted that physically, because the surface currents are stronger than the deep water formation rate and are driven primarily by different mechanisms, there isn’t a direct correlation between the decline in sinking and the slowdown of surface currents.

A review of a number of paleoclimatic studies puts the current slowdown into context below.

So what happens with a slowdown or collapse of the thermohaline circulation?… The answer is that to a large degree, we don’t really know – because it’s a question of time scale and how the ocean circulation and coupled ocean-atmosphere system will respond to the forcing. We probably don’t want to find out.

From the paleoclimate record, there seems to be some evidence that past massive glacial melt events may have led to large changes in the thermohaline circulation and may have also triggered periods of intense cold. This is one of the theories regarding the period known as the Younger Dryas (from about 12,000 to 13,000 years ago). It was a period for which, there is ample evidence of significant global cooling (particularly in Europe and Greenland), and it happened relatively shortly after the breakup of the major ice sheets that covered the world at the end of the last glacial maximum. The idea is that a huge flood of glacial meltwater rapidly freshened the high latitude oceans, shutting off the global thermohaline circulation, significantly weakening the Gulf Stream and leading Europe to become much colder – which then led to another positive feedback cycle of ice sheet growth. However, there are questions regarding whether there is adequate geomorphological evidence to support the mass flux of water that would be required. It’s also important to note that while the Gulf Stream does convey warm water to high latitudes in Europe, the reason for Europe’s comparative warmth at high latitudes has a great deal to do with the atmosphere, the direction of the prevailing winds, the geometry and topography of Europe and the tempering effect of the Atlantic. It should also be noted that like everywhere else on the planet, Europe has been warming – quite rapidly. Even if the Gulf Stream were to weaken substantially, these atmospheric and land surface effects are still present. Furthermore, even with a significant input of fresh water into the North Atlantic and Southern Oceans, given the current very large differences in surface temperature across the world ocean and the comparatively small salinity differences, it is a virtual certainty that our planet’s oceanic overturning circulation pattern will continue to be “thermally dominated” for the forseeable future.

In our current state, with the polar ice caps less than half the size they were during the Younger Dryas or last glacial maximum, it’s doubtful that even a very rapid warming event could generate enough meltwater to abruptly halt the Gulf Stream. Furthermore, there are widely documented increases in both atmospheric and marine temperatures in the recent past (including throughout Europe and the North Atlantic). So even though the volume flux of the Gulf Stream is slowing, the combination of direct heating and both oceanic and atmospheric advection are likely to continue to lead to aggregate warming.

The idea that the thermohaline circulation could shut down completely very quickly and plunge the world into another ice age was explored in the 2004 science fiction film, “The Day After Tomorrow”. The science in this film took a few ideas that were loosely based on actual science and blew them way out of proportion for dramatic effect. Films like this probably do more damage to the climate narrative than serve its purpose.

There is evidence the rate of deep water formation will continue to decline and that the Gulf Stream and some other components of the global “conveyor” will weaken. There are real concerns connected to sea level, oxygenation of the deep ocean and carbon balance as mentioned above. But the warming and extreme hydroclimate impacts already discussed are much more likely to dominate the global response. The likelihood of a transition to an abrupt ice age is effectively nill.