We know that human activity – specifically the combustion of fossil fuels, various agricultural practices and certain industrial processes are putting greenhouse gases into the atmosphere at a faster rate than they are removed by natural processes.

The chemistry on the combustion of fossil fuels is very simple and clear. Chemically speaking, fossil fuels are hydrocarbons. The burning/combustion chemical reaction adds oxygen to the substance being burned. While the exact stoichiometry varies by the chemical species, the chemical reactions are essentially hydrocarbon+heat+oxygen = carbon dioxide and water vapor+heat.

For methane, the simplest hydrocarbon (and the dominant component in natural gas), the reaction is

CH4+2O2 = CO2+2H2O

For octane (a common chemical component in gasoline for your car), the chemical reaction is a bit more complex.

2C8H18+ 25O2 = 16CO2+18H2O

Coal tends to have even longer/more complex hydrocarbon chains.

The longer/larger the hydrocarbon chain, the higher the mass ratio of carbon to hydrogen and the greater the amount of carbon dioxide produced from combustion. Consequently, natural gas is “cleaner” than oil which is “cleaner” than coal.

The link below shows information from the US Energy Information Administration on the carbon dioxide emissions by fuel type.

https://www.eia.gov/environment/emissions/co2_vol_mass.php

A description of the methodology is shown here:

https://www.eia.gov/environment/emissions/includes/methodology.php

Fossil fuels have become central to our economy for a number of essential reasons.

History and inertia: Our modern world created an infrastructure based on fossil fuels before the population was anywhere close to what it is today (the global population reached about 1 billion around 1800, 2 billion around 1930, 3 billion in 1960, but now stands at 8 billion). The first cars and planes were developed around the turn of the 20th century and a great deal of infrastructure was developed to support automobile (and air) traffic by the 1950s and 1960s. While there were scientists who understood the implications of climate change as early as the 1800s, their influence was limited and the ease and convenience of developing a transit and energy system based on fossil fuels was clearly a dominating force in the 1800s and early to mid 20th century. While there was some demonstrable evidence of climate change even in the earlier half of the 1900s, there was also a bit of a global cooling in the mid to late 1900s (1950s-1970s) and the real compelling evidence of climate change has been most conspicuous during my lifetime (since 1980). But at this point, as a species, we humans have built a deep state of dependence on a fossil fuel energy and transit infrastructure that will be extremely difficult and costly to change.

Economic development: Historically, countries that have used more energy per person have enjoyed a higher quality of life and more rapid economic development. While there are some wasteful countries that have a lower quality of life than their comparably emitting peers and there are some efficient countries that enjoy a higher economic dividend and quality of life than their similar emitting peers, this overall relationship is quite robust.

source: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/per-capita-fossil-energy-vs-gdp

Convenience: In addition to the inertia of the infrastructure for fossil fuels already being built, fossil fuels have the significant advantage of being relatively readily storable, transportable and energy dense. Solar energy and wind energy are highly intermittent. Hydropower has other environmental consequences and is very localized – requiring extensive transmission capabilities. Nuclear power has some environmental benefits, but also some issues with safety/security, the disposal and storage of nuclear waste – and nuclear energy doesn’t lend itself well to transportation and requires a similar transmission and distribution infrastructure to hydropower.

For vehicular transport, having a fuel source that is energy dense in liquid or solid form is highly advantageous.

While carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuel combustion are the dominant human source, it should also be noticed that land use changes and deforestation in particular are also very significant contributors to CO2 emissions. When trees die, not only is the carbon sink they provide through photosynthesis lost, but the organic carbon embedded in the body of the tree decomposes and some of that carbon does wind up in the atmosphere (although most winds up in other living things or in the soil).

In sum total, since the start of the Industrial Revolution, human beings have emitted about 2 trillion metric tons of carbon dioxide. Recent years have seen annual rates of emissions around 35-40 billion tons of CO2. This positively dwarfs the annual rate of emissions by volcanoes as shown in the graphic below.

Methane: Another critically important greenhouse gas is methane (CH4). While methane is produced naturally through the decay of organic matter, about half to 60% of methane emitted to the atmosphere in recent years has come from human sources. The concentration of methane in the atmosphere is far smaller than that of CO2, but it is a far more potent greenhouse gas per molecule. Agriculture accounts for almost half of human methane emissions and fossil fuel use another third. Food waste is another significant contributor to methane emissions.

Ozone: While ozone in the stratosphere is naturally occurring and acts as a protective barrier against harmful radiation, ozone in the lowest layer of the atmosphere (the troposphere) is an atmospheric pollutant, a greenhouse gas, and is harmful to human health, ecosystems and agricultural productivity. Tropospheric ozone is formed when carbon monoxide, volatile organic compounds (from tailpipe emissions) and nitrous oxides react chemically in sunlight and heat to form O3.

The reduction in the production of chlorofluorocarbons following the 1987 Montreal Protocol has helped significantly repair the hole in the stratospheric ozone hole. But the concentration of near surface and tropospheric ozone has steadily increased over time, because of the continued emissions from human industry and tailpipes. To learn more, consult https://www.ccacoalition.org/short-lived-climate-pollutants/tropospheric-ozone.

Nitrous oxide, NOx and fluorocarbons: Nitrous oxide (N2O), NOx and fluorocarbons are also greenhouse gases. While nitrous oxide and NOx occur naturally, as part of Earth’s nitrogen cycle, fluorocarbons are almost entirely manmade. Human sources of nitrous oxides generally consist of agricultural processes – particularly agricultural processes that use chemical fertilizers intensively. NOx gases are often produced as a byproduct of burning fossil fuels. Fluorocarbons are typically used in synthetic polymers, refrigerants and drugs. Per molecule, fluorocarbons have the most potent greenhouse effect of the any of the chemicals discussed on this page. But thankfully, they also exist in the smallest concentration in the atmosphere by a large margin – so their total contribution to the Earth’s warming is limited.

To learn more about N2O, consult https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/overview-greenhouse-gases#nitrous-oxide

To learn more about NOx, consult https://scied.ucar.edu/learning-zone/air-quality/nitrogen-oxides

To learn more about fluorocarbons, consult https://www.epa.gov/ghgreporting/fluorinated-greenhouse-gas-emissions-and-supplies-reported-ghgrp.

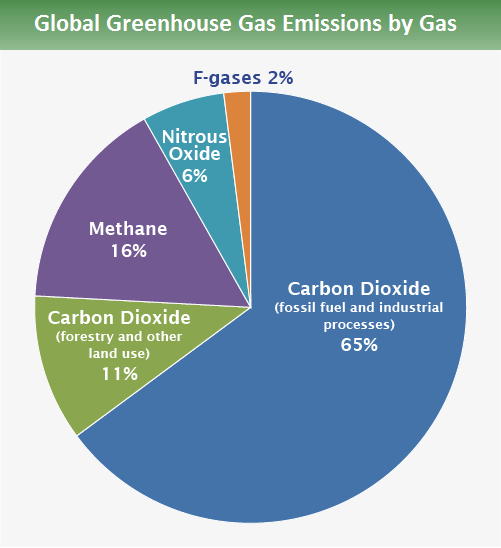

The total global contribution to GHG by type of GHG (as of 2015) is shown below

source: https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/global-greenhouse-gas-emissions-data

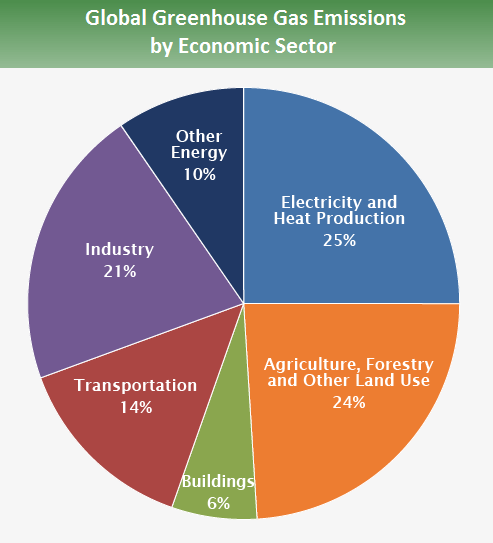

and by economic sector is shown below

source: https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/global-greenhouse-gas-emissions-data