Atmospheric Fundamentals

Chemically, the atmosphere is comprised mostly of nitrogen (about 78%) and oxygen (about 21%) with much of the remainder being argon. These gases do not cause a greenhouse effect. But water vapor, carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, tropospheric ozone and fluorocarbons do cause the greenhouse effect. A pie chart of the chemical composition is shown below.

source: https://scied.ucar.edu/learning-zone/air-quality/whats-in-the-air

The atmosphere can be thought of as having five layers (https://scied.ucar.edu/learning-zone/atmosphere/layers-earths-atmosphere):

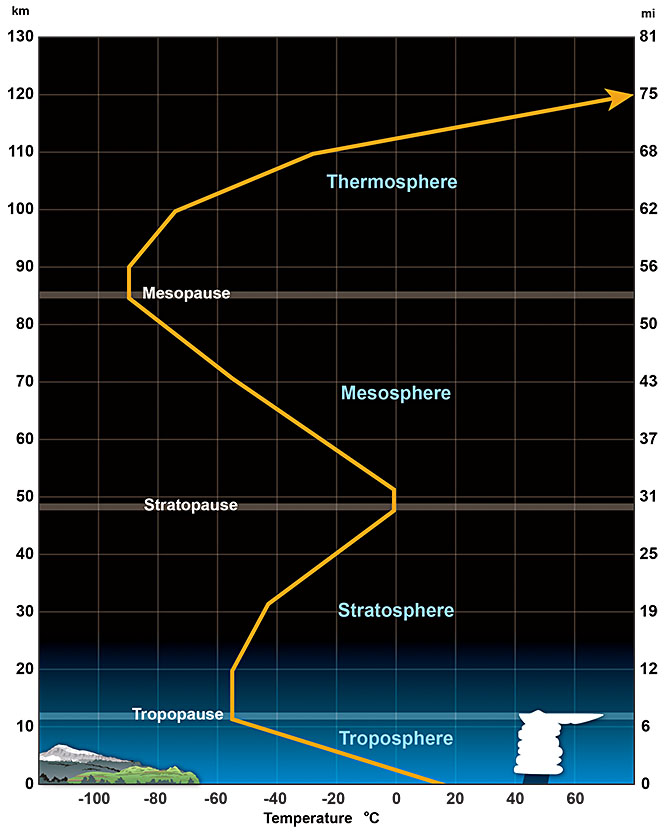

1) the troposphere or lowest layer – which extends from the surface to about 10 km or 6.5 miles. While being the smallest layer, this layer is by far the layer with the most mass, largest number of molecules, the most water vapor and pretty much all weather. Over 80% of the total mass of the atmosphere is in the troposphere and about half of the mass of the atmosphere is below about 5.5-6 km. The troposphere is characterized by a negative temperature lapse rate (i.e. the temperature decreases as one ascends).

2) the stratosphere which extends from the “tropopause” (top of troposphere bottom of stratosphere) up to about 50 km (or 31 miles). The stratosphere contains almost all the rest of the remaining mass of the atmosphere – with very little mass in the outer three layers despite their size. While weather and clouds are relatively rare in the stratosphere, individual major thunderstorms or hurricanes can create enough vertical cloud development to make cloud tops penetrate (sometimes quite far) in to the stratosphere. Supersonic jets sometimes travel in the upper stratosphere and sometimes higher. Many commercial passenger airplanes travel in the lower stratosphere near the tropopause – because there is less turbulence and weather than the upper troposphere. The stratosphere contains an important layer of ozone that helps shield the planet from harmful ultraviolet radiation from the sun. Almost all the water vapor in the atmosphere is found in the troposphere, but almost all of the 1% that isn’t in the troposphere is in the stratosphere. The temperature lapse rate in the stratosphere is positive (i.e. the temperature increases as one ascends).

3) the mesosphere which extends from the stratopause up to about 80 km (50 miles). The air in the mesosphere is extremely thin and many meteors burn up in the mesosphere. The temperature lapse rate in the mesosphere is negative.

4) the thermosphere which extends from the mesopause up to about 700 km (440 miles). The air density in the thermosphere and exosphere is so thin that one could consider much of the thermosphere and exosphere part of space more than the Earth’s atmosphere. Many satellites operate in the thermosphere and this layer of the atmosphere is bombarded with high energy UV waves from the sun – leading the temperature to increase with height (positive lapse rate). This high energy bombardment causes many atoms in the thermosphere, exosphere and even mesosphere to lose their electrons and become ions – making these upper layers of the atmosphere collectively known as the ionosphere. The excitation of these ions during periods of high solar activity by the strong magnetic field of the world’s polar regions is known to create the phenomenon of auroras. While the temperature at the very top of the thermosphere is very high (temperature is a metric of the speed at which the air molecules move), the extremely low density of particles implies that this region would still “feel” very cold to an entity accustomed to the density of air at the surface of the Earth.

5) the exosphere which extends from the top of the thermosphere upward to space. The exact boundary between the top of the exosphere and space is unclear and disputed and as mentioned above, many would even consider parts of the thermosphere part of space. The exosphere has a negative lapse rate and the natural temperature of interstellar/interplanetary space is very cold – just a few degrees Kelvin.

The figure below shows the average temperature with altitude in the atmosphere up to the lower thermosphere.

source: https://www.noaa.gov/jetstream/atmosphere/layers-of-atmosphere

Motions in the atmosphere are governed by the ideal gas law which states that

PV = nRT

where P is the pressure, V is the volume, T is the absolute temperature, R is a constant and n is the number of molecules of gas. The density of air decreases strongly with height as mentioned above. Near the surface, differential heating causes air to expand and rise (increase in T leads to an increase in V at a comparable P). This vertical motion is known as convection and drives much of the weather seen on the planet. Often with the expansion/rising motion associated with convection, there is a slight decrease in pressure at the surface, setting up a pressure gradient that drives horizontal winds. So the warm temperature anomaly is manifested by a significant increase in volume and slight decrease in pressure.

Conversely, areas that are anomalously cold relative to their surroundings, air parcels tend to contract and “sink” – and the sinking motion tends to slightly elevate surface pressure relative to surroundings. These patterns are partly responsible for the global atmospheric motions described on other pages with rising motion along the near equatorial zone of intertropical convergence, subsiding motion in the subtropics, another zone of rising motion and stormy activity along the polar front and sinking motion and very cold, dry conditions at the poles.

Radiative Balance

If there were no greenhouse gases in the Earth’s atmosphere (or if there were no atmosphere), the Earth would be much colder than it is. In fact, with no greenhouse gases or no atmosphere at all, the Earth’s average surface temperature would be about 255 Kelvin or -18 Celsius or about 0 Farenheit. This is much colder than the actual observed global mean temperature (although anecdotally, it is actually quite close to the average between the highest and lowest temperatures ever recorded on the surface of the Earth (about 134F/57C and -129F/-90C, in Death Valley, California and Vostok Station, Antarctica respectively). But the actual observed global mean temperature across all locations, seasons and times of day is around 15C or 288K or 59F. So the warming impact of the greenhouse gases is about 33C/59F.

Greenhouse gases constitute less than 1% of the atmosphere. In addition to being a greenhouse gas, carbon dioxide plays a critical role in photosynthesis – so chemically, the Earth would not have plants or photosynthetic bacteria as we know them without carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. But leaving the chemistry aside, the considerably colder temperature of an Earth without greenhouse gases would imply that much less of the Earth’s surface water would be liquid, and many regions of the planet would experience temperatures below freezing for most of the year. This more inhospitable climate would imply that there could be far fewer plants and animals on earth and the species that did exist would have to be much better adapted to cold. Human beings might not have evolved on such a planet (the earliest human ancestors classified as homo sapiens lived in the tropical savannas of East Africa).

This significant warming effect of the greenhouse gases (33C/59F) is a result of the greenhouse gases absorbing outgoing long-wave radiation from the Earth’s surface. The geothermal heat flux from the surface of the Earth is not zero, but is very small except in volcanically active regions and the Earth does not generate it’s own energy from a process like nuclear fusion. So in order for the surface of the Earth to be in energetic equilibrium, the amount of energy it absorbs from the Sun and the atmosphere must be balanced by the amount of energy emitted from the surface. Greenhouse gases are mostly transparent to incoming solar shortwave radiation, but absorb considerably more of the Earth’s outgoing long-wave radiation. A portion of this outgoing long-wave radiation is then sent back to the surface. The larger the share of the outgoing long-wave radiation that is absorbed by the atmosphere and sent back to the surface, the more energy the surface must emit to compensate. This radiative energy is strictly a function of the surface temperature – so more energy emitted translates to higher observed temperatures.

A simple heuristic model of the physics is described on the code and equations page. The overall picture of the atmosphere’s energy fluxes is shown below with breakdowns of how much solar energy is reflected and absorbed by the surface and the atmosphere, how much energy is emitted by the atmosphere in different directions and how much heat is exchanged through evapotranspiration and sensible/thermal heat exchange.

Note that for the “thermals” or sensible heat and latent heat /evapotranspiration terms represent a net transfer of energy from the surface to the atmosphere. Some energy is required by the surface layer atmosphere to induce convection to move warm air to higher elevations, but more energy is released by that air to the atmosphere when it does, because at higher elevations, the ambient air is colder, so the temperature differential is greater. Some energy is required by the (warm) surface atmosphere to induce evapotranspiration but more energy is released to the atmosphere when precipitation/condensation occurs for the same reason regarding the colder ambient air temperature at the level of condensation/precipitation.

https://scied.ucar.edu/image/radiation-budget-diagram-earth-atmosphere

Because the Earth does not generate a significant amount of it’s own heat from a process like fusion (and geothermal heat flux from the surface is very small), the amount of energy the surface of the Earth radiates outward must balance the amount of energy it receives. Solar energy comes to the earth in high energy/short wavelength form and the Earth radiates energy at longer wavelengths.

Greenhouse gases do not absorb much of any of the Sun’s incoming shortwave radiation. But they do absorb a significant amount of the outgoing longwave radiation from the Earth’s surface in the atmosphere and then a substantial part of this energy is re-radiated back to the Earth’s surface. This re-radiated energy is added as an energy flux into the Earth’s surface, driving up the amount of energy the surface must emit to be in equilibrium. The stronger this effect is, the more the temperature will rise.

A very extreme example of this effect is our planetary neighbor closer to the Sun, Venus. Venus is the hottest planet in the solar system by far despite being almost twice as far from the Sun as the first planet Mercury. Venus also reflects much more of the incoming sunlight that falls on it than does Earth (75% for Venus as compared to about 30% for Earth). But Venus has such a thick, absorbent atmosphere that it absorbs well over 99% of the energy emitted by the surface and the Venusian atmosphere directs almost all of that absorbed energy (also over 99%) back to the surface. The average temperature on Venus is 465 C or over 800F! This very high emission temperature, high reflectivity of solar radiation and proximity to Earth are why Venus glows so brightly in the night sky. This thermal effect is known as a “runaway greenhouse effect”. If Venus were the same distance from the Sun and reflected the same share of sunlight, but had no greenhouse gases in it’s atmosphere, the equilibrium temperature would actually be colder than the equilibrium no atmosphere version of Earth at about 222K or -46C. And yet, the role of Venus’s atmosphere warmed the surface of the planet by 500C relative to that baseline and has made its surface hot enough to melt lead.

Mercury can of course get very hot, especially during it’s very long day, especially near the equator. But it’s atmosphere is much thinner and does not retain nearly as much of the energy that is absorbed by the surface – so the global mean temperature on Mercury is much cooler, although still much hotter than Earth at 167C.

The main and naturally occurring greenhouse gases are water vapor (H2O), carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), and nitrous oxide (N2O). While human activity has added considerably and directly to the concentration of carbon dioxide and methane, there was a concentration of these gases in the atmosphere before humans came along. Other greenhouse gases (with an almost entirely or entirely human origin) include tropospheric ozone (O3) and chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and other halocarbons.

Of all the greenhouse gases, water vapor has the largest total impact and the highest concentration, followed by carbon dioxide, methane, ozone, halocarbons and nitrous oxide. Halocarbons have the greatest impact per molecule, but also have the smallest concentration. The amount of water vapor in the atmosphere is very strongly connected to the atmospheric temperature through the Clausius Clapeyron relationship. While human activity adds little if any water vapor to the atmosphere directly, the rising temperatures do cause more water vapor to be evaporated and held as vapor. But because this is an indirect effect and something we cannot control, we do not consider water vapor to be a greenhouse gas that we can regulate. Carbon dioxide has the largest impact and the largest concentration and is inextricably linked to the burning of fossil fuels for energy.

The table and diagram below help explain the current concentrations of the greenhouse gases, how much their concentration has changed since the Industrial Revolution and the estimated radiative forcing of different human and natural activities.

| current concentration (by volume) | % increase since Industrial Revolution | |

| H2O (water vapor) | 0.4% | about 5% |

| CO2 (carbon dioxide) | 0.0417% (about 417 ppmv) | about 50% |

| CH4 (methane) | 0.00019% (about 1.9 ppmv) | about 160% |

| N2O (nitrous oxide) | 0.000033% (about 330 ppbv) | about 20% |

| O3 (ozone) | 0.0000025%+/- 0.0000005% (20-30ppbv) | at least 100%, possibly much higher |

| halocarbons | concentrations depend on the specific gas, but the most abundant (CFC12) has a concentration of about 500 pptv or 0.00000005% | infinite – did not exist in the atmosphere before human activity |

https://www.epa.gov/climate-indicators/climate-change-indicators-climate-forcing

Different greenhouse gases absorb energy in different parts of the electromagnetic spectrum. These differential absorption characteristics imply that some GHG’s absorb energy in bands that are mostly being transmitted, so further addition of those GHGs is especially harmful. Some GHGs absorb energy in wavelength bands that are already largely “saturated”, somewhat limiting their effect. The differences between these absorption spectrum effects, coupled with the differences in concentration and the differences in atmospheric residence time explain the differences in the “global warming potential” of adding another molecule of CFCs, vs. methane vs. CO2. These differences in the absorption spectrum are depicted in the figure below.

https://ei.lehigh.edu/learners/cc/greenhouse/greenhouse1.html

For more information about radiative forcing of greenhouse gases, the webpage below is a good link.