The daylength and insolation at the top of the atmosphere (amount of solar energy received by a designated location) are both strictly a function of latitude and time of year. While the code below does not account for nuanced differences in sunrise and sunset times due to idiosyncracies of the time zone, the slight extension of day length because of the curvature of the Earth or the modulation of surface insolation as a function of reflected light, cloud cover, etc., the day length, sunset and sunrise times, and top of atmosphere insolation values for noon are all calculated using the day of the year and latitude as inputs.

The days variable indicates the number of days after the winter solstice for the date in question. The latitude values for this code range from 0 to 90 degrees and for locations in the southern hemisphere, the user changes the days variable accordingly (i.e. for New York (latitude 40N) on April 21, the inputs would be days = 121 (days since December 21), latitude = 40, whereas for the same date in Buenos Aires (30S), the inputs would be days = 304 (days since June 21), latitude = 30).

Here I am considering the “declination angle” to be the northward displacement of latitude because of the tilt of the Earth. It reaches a peak value of 23.5 degrees on the solstice of December 21 and minimum value of -23.5 on June 21 and to first approximation, the effective declination varies over the year with the cosine of the day*2*pi/360 because of the revolution of the Earth around the Sun.

For a given location, the noonangle = latitude + declination and the midnightangle = latitude-declination. So for New York City, the effective latitude or noon angle on December 21 is about 64N and the midnight angle is 17N, whereas on June 21, the noonangle is about 17N and the midnight angle is 64N. Locations in the tropics cross the plane of the ecliptic from day to night and latitudes poleward of the Arctic or Antarctic circles are in permanent dark or permanent day around the time of the solstices.

For a given latitude, in order to figure out how much of the 24 hours is in daylight, one must figure out how much of the 24 hours the location spends on the “day half” of the earth as that location rotates around the revolution axis at a tilt. The first step to doing this is to consider the Earth in “profile”. This is easier to illustrate with a picture below. Imagine the Sun being to the left of the picture and North being up.

This is a diagram of the Earth in northern hemisphere winter. The point in the top right quadrant where the green dotted line meets the circle is the North Pole and the point in the bottom left quadrant where the green dotted line meets the circle is the South Pole. All points to the right of the black vertical line will be in the Earth’s shadow (i.e. night), whereas all points on the left side will be in sunshine (i.e. day). Over the course of the day, every point on earth travels around a circle on a slant that is perpendicular to the rotation axis.

Here in profile view, those rotation paths are denoted by slanted lines. The path described by points on the equator is depicted by the blue dashed line and the path described by the point of interest (mid-latitudes northern hemisphere) is depicted by the solid purple line). The noon angle is the angle between the brown and red lines – i.e. the “effective latitude” of the chosen location at noon with the plane of the ecliptic being the “effective equator”. The midnight angle is the angle between the solid green line and the red line. Here, “midnight” and “noon” do not refer directly to exact clock time, but to the effective concepts of the exact middle of the day and the exact middle of the night. Note that more of the purple line is to the right of the black line (i.e. night) than to the left of the black line (i.e. day).

A first approximation to the daylength would be to calculate the fraction of the purple line that is to the left of the day/night divide. It can be shown geometrically that this is the ratio of the cosine of the noon angle divided by the sum of the cosines of the noonangle and the midnight angle (considering the noon and midnight angles to both be between 0 and 90 degrees).

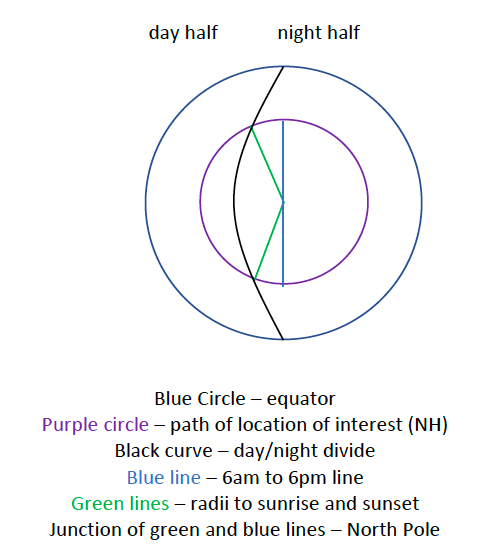

While this is a first approximation, it isn’t quite accurate, because the location of interest rotates around a circle on a slant in three dimensional space over the course of the day. That slant is depicted in 2d profile by the purple line. But if we then look “down” on the earth from a polar view and consider the path of the latitude of interest, it describes a circle, but the day/night divide is not in the “center” because the North Pole is experiencing permanent night at this time of year. The figure below describes the scenario (again considering the Sun to be to the left).

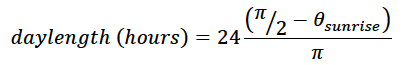

The larger blue circle is the equator. The black curve demarcates the day/night divide. Note that in polar projection, this is a curve because for higher latitudes, the days are very short, whereas for the equator, the day and night are the same length. In this polar projection, the North Pole is in the middle (where the green and blue lines meet) and circles closer to the center represent higher latitudes, while circles further away from the center represent lower latitudes. Because we are considering a date in Northern Hemisphere winter, the North Pole and the highest latitudes are entirely on the night side of the black curve. The smaller, purple circle is the path taken by the location of interest in the northern hemisphere over the course of 24 hours – clearly more than 12 hours are night and less than 12 hours are day. The blue line is the “effective” 6AM to 6PM line and the green radius lines connect to the purple circle at sunrise and sunset. The angle between the green and blue lines is something here denoted as thetasunrise which indicates how much of the circle is in the day time and how much is in the night. It can be shown geometrically that this is equal to

This gives the sunrise angle in radians. Note that during the “winter half” of the year from autumn to spring equinoxes, the cosine of the noonangle is less than half of the total of the sum of the cosines and so thetasunrise is positive. During the “summer half” of the year from the spring to fall equinoxes, the cosine of the noonangle is more than half of the sum and so thetasunrise is negative.

The daylength in hours is 24 multiplied by the ratio of the arc length in daytime to the total circumference of the circle. The total circumference of the circle is 2*pi. The arc length in day time is 2*(pi/2-thetasunrise). So the resulting daylength in hours is

The sunrise and sunset times relative to “solar noon” are (in military time) 12-daylength/2 and 12+daylength/2, respectively.

The code below calculates the same as the above, but in degrees, rather than radians.

The insolation (top of atmosphere radiation) at “solar noon” (the time of day when the sun is most directly overhead can be calculated as

where S is the solar constant 1364 Wm-2. The intensity of solar radiation peaks at noon and is zero at sunrise and sunset. For all location across the Earth, the intensity of solar radiation over the course of the day is a convex function (i.e. there is less absolute variability in insolation between 11AM and noon than between sunrise and an hour after sunrise). But the degree of that convexity and the specific shape of the insolation curve as a function of time through the day is not a strictly sinusoidal function and depends in more complex ways on latitude and season. At the equator on the equinoxes, it is a perfect sine curve.

Note that in all of these considerations, there are parts of the world (poleward of the Antarctic and Arctic circles) that experience constant sunshine or constant darkness for parts of the year. These distinctions are taken into account in the codes below.

R script

#This is a script that takes a latitude (lat)

#and date (days after winter solstice) and time

#(hour of the day in military time) and produces

#max insolation, daily integrated solar

#radiation and instantaneous insolation at the

#top of atmosphere. Note that the sunrise and

#sunset times given here are the sunrise and

#sunset relative to the effective noon - not the

#clock time - as that is effected by both

#longitude, nuances of local time zones and the

#curvature of the Earth/extension of sunrise and

#sunset. The user can define the number of

#experiments (n), but either days or latitude

#should be fixed, with the other being a simple

#vector

n = 3

days = 170

lat = c(20, 41, 78)

dec <- 23.5*cos(days*pi/182.5)

noonang <- lat+dec

midnightang <- lat-dec

cosratprelim <- cos(noonang*pi/180)/(cos(midnightang*pi/180)+cos(noonang*pi/180))

print(cosratprelim)

for (i in 1:n)

if (cosratprelim[i]>=0) {cosratprel[i] = cosratprelim[i]} else {cosratprel[i] = 0}

print(cosratprel)

for (i in 1:n)

if (cosratprelim[i]<1) {cosrat[i] = cosratprel[i]} else {cosrat[i] = 1}

print(cosrat)

radatdusk <- asin((0.5-cosrat)/0.5)*180/pi

shofday <- 2*(90-radatdusk)/360

daylength <- shofday*24

print(paste('daylength',daylength))

sunrise <- 12-0.5*daylength

sunset <- 12+0.5*daylength

print(paste('sunrise',sunrise))

print(paste('sunset',sunset))

#Note that the true sunrise and sunset times

#differ by longitude and are also influenced by

#the curvature of the earth and the

#peculiarities of the time zone. The values

#calculated here are on a 24 hour clock relative

#to the "solar midnight"=0 and "solar noon"=12.

Inoon <- max(1364*cos(noonang*pi/180),0)

print(paste('Inoon',Inoon))

Python script

#This is a script that takes a latitude (lat)

#and date (days after winter solstice) and time

#(hour of the day in military time) and produces

#max insolation, daily integrated solar

#radiation and instantaneous insolation at the

#top of atmosphere. The default is for 6PM on

#June 17th at 41 N. You can change the number of

#latitudes or number of days, but not both.

n = 3

days = 170

lat = [20 41 78]

import xarray

import numpy as np

import pandas

import math

dec = 23.5*np.cos(np.multiply(days,(math.pi/182.5)))

noonang = np.add(lat,dec)

midnightang = np.subtract(lat,dec)

cosratprelim = np.cos(np.multiply(noonang,(math.pi/180)))/((np.cos(np.multiply(midnightang,(math.pi/180))))+(np.cos(np.multiply(noonang,(math.pi/180)))))

print(cosratprelim)

cosratprel = np.zeros(n)

cosrat = np.zeros(n)

for i in range(0,n):

if cosratprelim[i]>=0:

cosratprel[i]=cosratprelim[i]

else:

cosratprel[i]=0

print(cosratprel)

for i in range(0,n):

if cosratprelim[i]<1:

cosrat[i]=cosratprel[i]

else:

cosrat[i] = 1

print(cosrat)

radatdusk = np.multiply((np.arcsin(np.divide((np.subtract(0.5,cosrat)),0.5))),(180/math.pi))

shofday = 2*(90-radatdusk)/360

daylength = shofday*24

print('daylength',daylength)

sunrise = 12-0.5*daylength

sunset = 12+0.5*daylength

print('sunrise',sunrise)

print('sunset',sunset)

# Note that the true sunrise and sunset times

#differ by longitude and are also influenced by

#the curvature of the earth and the

#peculiarities of % the time zone. The values

#calculated here are relative to the "solar

# midnight" = 0 and "solar noon" = 12.

Smax = np.zeros(n)

S12 = 1364*np.cos(noonang*(math.pi/180))

#print(S12)

for i in range(0,n):

if S12[i] >=0:

Smax[i] = S12[i]

else:

Smax[i] = 0

print('Smax',Smax)

Matlab script

% This script takes a latitude and date (expressed in days after the winter

% solstice) and time (in hours after midnight) and returns the daylength.

% The default latitude is 41 N, day is June 17 and time is 6 hours after midday.

n=3

days = 170

lat = [20 41 78]

dec = 23.5*cos(days*pi/182.5)

noonang = lat+dec;

midnightang = lat-dec;

cosratprelim = cos(noonang*pi/180)./(cos(midnightang*pi/180)+cos(noonang*pi/180));

for i = 1:n;

if cosratprelim(i)>=0, cosratprel(i) = cosratprelim(i), else cosratprel(i) = 0;

end

end

for i = 1:n;

if cosratprelim(i)<1, cosrat(i) = cosratprel(i), else cosrat(i) = 1;

end

end

radatdusk = asin((0.5-cosrat)/0.5)*180/pi;

shofday = 2*(90-radatdusk)/360;

dayl = shofday*24

sunrise = 12-0.5*dayl

sunset = 12+0.5*dayl

% Note that the true sunrise and sunset times differ by longitude and are

% also influenced by the curvature of the earth and the peculiarities of

% the time zone. The values calculated here are relative to the "solar

% midnight' = 0 and "solar noon" = 12.

S12 = max(1364*cos(noonang*pi/180),0)