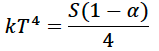

The equilibrium temperature of a planet without an atmosphere can be determined from relatively simple physics. A planet is considered a “blackbody” and the outgoing radiated energy is equal to kT4, where k is the Stefan Boltzmann constant of 5.67*10-8Wm-2K-4 and T is the absolute temperature in Kelvin. This outgoing energy must balance the incoming energy from the star (in our solar system’s case, the Sun).

At the distance between the Sun and the Earth, the solar energy flux or “solar constant”, sometimes denoted by S is about 1364 Wm-2. A fraction of this energy (about 30%) is reflected by the surface and the atmosphere – this is called the planetary “albedo” and is often symbolized by 𝛼. The area of solar flux energy the Earth intercepts is the area of the circle with the radius of the Earth πrearth2. But that energy is distributed across the entire surface of the Earth which is, to first approximation a sphere with area 4πrearth2. So the actual average solar energy flux incident on the surface of the Earth is S(1-𝛼)/4, which translates to about 239 Wm-2 – the same value seen in the outgoing top of atmosphere radiation from the radiative balance page. Note that the energy distribution is asymmetric – there is no energy incident on the night half of the Earth and the solar radiation is much stronger closer to the equator or effective equator for the date in question and diminishes towards the poles. Incident solar radiation is also at a peak at noon and diminishes in early morning and late afternoon/evening.

In the case of no greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, we simply set these two quantities equal to each other

and we have an equilibrium temperature of 255K = -18C = 0F as described in the radiative balance page.

While truly understanding atmospheric dynamics is very involved and the characterization of radiation in global climate models is very complex, this page presents a simplistic “one-layer” atmosphere heuristic model. As mentioned in the atmospheric fundamentals and radiation page, there are five layers to the atmosphere characterized by switches in the lapse rate and other important changes in characteristics. But for the purposes of this page, I am considering the atmosphere primarily as the troposphere and have a negative lapse rate. This heuristic model does recreate the stratospheric cooling that is observed as the climate has changed.

Note that reflected radiation from the Sun does not participate in the energy balance within the atmosphere or the surface of the Earth.

In this simplistic model, there are three “layers”: 1) the Earth’s surface the 2) Earth’s atmosphere (effectively the troposphere) and 3) space (effectively the stratosphere). The radiated energy upward from the surface determines the surface temperature by the Stefan Boltzmann law and the energy radiated upward to space by the atmosphere determines the effective aggregate atmospheric temperature. The incoming energy from the Sun is balanced by the sum of the radiation from the atmosphere to space and the small amount of surface radiation (atmospheric window) that escapes to space. At each “layer” there must be an energetic balance.

There are eight “fluxes” to consider:

1) the share of incident solar radiation that is reflected to space (𝛼S/4),

2) the share of incident solar radiation that is absorbed by the atmosphere (f1S(1-𝛼)/4), where f1 is a fractional parameter,

3) the share of the incident solar radiation that is absorbed by the surface ((1-f1)S(1-𝛼)/4),

4) the share of the outgoing surface radiation absorbed by the atmosphere (f2kTs4) where Ts is the temperature of the surface in Kelvin and f2 is another fractional parameter,

5) the share of outgoing surface radiation that goes straight to space (sometimes referred to as the “atmospheric window” ((1-f2)kTs4),

6) the sensible and latent fluxes (L) from surface to atmosphere.

7) the share of total atmospheric energy flux (Ea) that is radiated downward to the surface (f3Ea) where f3 is another fractional parameter and

8) the share of atmospheric radiation that is radiated upward to space which leads to the radiating temperature at the top of the atmosphere Ta ((1-f3)Ea = kTa4).

We have three equations for equilibrium: the energy balances at the surface, the atmosphere and space. The reflected energy does not play a role in the energy balance.

Surface equation

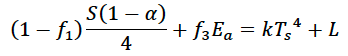

The solar radiation absorbed by the surface plus the atmospheric radiation sent to and absorbed by the surface must balance the total upward longwave radiation and sensible/latent fluxes by the Earth’s surface, or:

Atmosphere equation

The solar radiation absorbed by the atmosphere plus the surface radiation absorbed by the atmosphere plus the sensible/latent heat fluxes must balance the total atmospheric radiation, or:

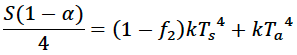

Space equation

The total solar energy absorbed by the surface and atmosphere must be balanced by the energy emitted to space from the surface and from the top of the atmosphere, or:

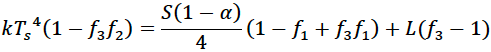

Using the LHS of the atmosphere equation to substitute for Ea in the surface equation, we can restate the surface equation entirely in terms of Ts

This can be rearranged to

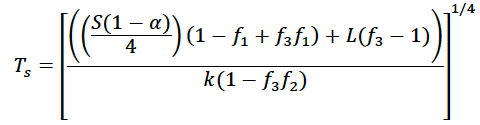

This can be further rearranged to give the surface temperature in terms of other parameters

Surface Temperature

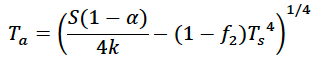

From the space equation, we have a simple relationship between the temperature at the top of the atmosphere and the surface

Top of Atmosphere Temperature

It’s clear from this atmospheric temperature equation that as the surface temperature increases, the top of atmosphere radiating temperature decreases. This makes intuitive sense as a higher surface temperature essentially implies stronger heat exchange between the surface and atmosphere with less energy being radiated to space directly by the atmosphere. The effective “radiating level” of the atmosphere is often considered to be the middle to upper “troposphere” (the lowest and densest layer of the atmosphere). Accordingly, the next higher layer (the stratosphere) has been observed to have cooled as the planet has warmed.

The table below explains the effects of different variables on both the surface temperature (Ts) and the atmospheric temperature (Ta) from the above equations. The fluxes from which the values are derived are on the radiative balance page.

| variable | current approximate value | effect of increase on Ts | effect of increase on Ta | tendency in a warmer climate |

| alpha (albedo) | 0.3 or 30% | cools | cools | decreases |

| sensible and latent heat flux (L) | 97 Wm-2 | cools | heats | increases |

| atmospheric absorption of solar radiation (f1) | 0.326 (78Wm-2 of the incoming 239Wm-2 of SW radiation are absorbed) | cools | heats | no significant change |

| atmospheric absorption of outgoing longwave radiation (f2) | 0.944 (374Wm-2 of the outgoing 396Wm-2 of OLR are absorbed) | heats | heats | increases |

| share of atmospheric radiation directed back to surface (f3) | 0.605 (of the atmospheric radiation 333Wm-2 are radiated to the surface, while 239Wm-2 are radiated to space) | heats | cools | increases |

The albedo of the surface tends to decrease in a warmer climate because of the ice-albedo feedback, discussed on the feedback mechanisms page. The sensible and latent heat exchange tend to increase in a warmer climate because warmer air holds more water vapor (because of the Clausius Clapeyron relationship). This is a more complex feedback because clouds also have complex reflective properties and because water vapor itself is a greenhouse gas, thereby tending to increase f2. A warmer climate is not necessarily thought to influence the absorption rate of incoming solar radiation that much. But a climate with more greenhouse gases will definitely increase the rate at which the atmosphere absorbs outgoing longwave radiation and the proportion of atmospheric energy that is radiated to the surface. These effects will not “run away” to the degree that they did on Venus, no matter how rapidly we burn fossil fuels. But even modest changes in parameters f2 and f3 can have significant impacts on the Earth’s mean temperature, with many associated problematic consequences.

There are uncertainties in the sensitivity of all of these parameters to a warmer planet with more GHGs – which is part of what has made the overall “climate sensitivity” or amount of equilibrium temperature increase from a doubling of CO2 so difficult to constrain.

R script

#This script solves for the planetary mean temperature with specified parameters.

#The default parameters are those for Earth.

# solar constant for Earth in W/m^2

S <- 1364

#distance from Sun in AU. 1 AU = distance from Earth to Sun or 93 million miles.

AU <- 1

#solar constant for planet of interest

Sp <- S*(1/AU)^2

#albedo

alpha <- 0.3

#Stefan Boltzmann constant

k <- 5.67*10^(-8)

#sensible and latent heat exchange

L <- 97

#surface temperature with no atmosphere in Kelvin

TsnoA <- ((Sp*(1-alpha))/(4*k))^(1/4)

print(paste('TsnoA',TsnoA))

TsnoAC <- TsnoA-273.15

print(paste('TsnoAC',TsnoAC))

#share of non-reflected solar radiation absorbed directly by atmosphere

f1 <- 0.326

#share of longwave radiation absorbed by atmosphere

f2 <- 0.944

#share of atmospheric radiation sent to surface

f3 <- 0.605

Ts <- (((Sp*(1-alpha)/4)*(1-f1+f3*f1)+L*(f3-1))/(k*(1-f3*f2)))^(1/4)

print(paste('Ts',Ts))

TsC <- Ts-273.15

print(paste('TsC',TsC))

Ta <- ((Sp*(1-alpha)/(4*k))-(1-f2)*Ts^4)^(1/4)

print(paste('Ta',Ta))

TaC <- Ta-273.15

print(paste('TaC',TaC))

Python script

#This script solves for the planetary mean temperature with specified parameters. The default values are those for Earth

# solar constant for Earth in W/m^2

S = 1364

#distance from Sun in AU. 1 AU = distance from Sun to Earth or 93 million miles.

AU = 1

#solar constant for planet of interest

Sp = S*(1/AU)**2

#albedo

alpha = 0.30

#Stefan Boltzmann constant

k = 5.67*10**(-8)

#sensible and latent heat exchange

L = 97

#surface temperature with no atmosphere in Kelvin

TsnoA = ((Sp*(1-alpha))/(4*k))**(1/4)

print('TsnoA', TsnoA)

TsnoAC = TsnoA-273

print('TsnoAC', TsnoAC)

#share of solar radiation absorbed directly by atmosphere

f1 = 0.326

#share of longwave radiation absorbed by atmosphere

f2 = 0.944

#share of atmospheric radiation sent to surface

f3 = 0.605

Ts = (((Sp*(1-alpha)/4)*(1-f1+f3*f1)+L*(f3-1))/(k*(1-f3*f2)))**(1/4)

print('Ts',Ts)

TsC = Ts-273.15

print('TsC',TsC)

Ta = (((Sp*(1-alpha))/(4*k))+(1-f2)*Ts**4)**(1/4)

print('Ta',Ta)

TaC = Ta-273.15

print('TaC',TaC)

Matlab script

%This script solves for the planetary mean temperature with specified

%parameters. The default parameters are those for Earth.

% solar constant for Earth in W/m^2

S = 1364;

%distance from Sun to planet in astronomical units (distance from Sun to Earth or 93

%million miles = 1 AU)

AU = 1;

%solar constant for planet of interest

Sp = S*(1/AU)^2;

%albedo

alpha = 0.3;

%Stefan Boltzmann constant

k = 5.67*10^(-8)

%sensible and latent heat exchange

L = 97

%surface temperature with no atmosphere in Kelvin

TsnoA = ((Sp*(1-alpha))/(4*k))^(1/4)

TsnoAC = TsnoA-273.15

%share of solar radiation absorbed directly by atmosphere

f1 = 0.326;

%share of longwave radiation absorbed by atmosphere

f2 = 0.944;

%share of atmospheric radiation sent to surface

f3 = 0.605;

Ts = (((Sp*(1-alpha)/4)*(1-f1+f3*f1)+L*(f3-1))/(k*(1-f3*f2)))^(1/4)

TsC = Ts-273.15

Ta = (((Sp*(1-alpha))/(4*k))-(1-f2)*Ts^4)^(1/4)

TaC = Ta-273.15