Biomass and biofuel refer to the burning of biological matter for energy. While this is the oldest form of energy production and was the dominant form of energy production prior to the Industrial Revolution, biomass and biofuels typically account for about 10-13% of global energy production worldwide – with the vast majority coming from biomass rather than biofuels.

To clarify the distinction between these energy sources, biomass generally refers to the burning of biological/organic material that is in a process of decay (sewage, food waste, leaves, grass, wood, etc.) that is unprocessed and usually (but not always) solid. The burning of biomass is relatively inefficient and the energy that is released from the burning of biomass is usually from burning the methane of decomposition. While this organic matter took carbon out of the atmosphere to begin with, the combustion of biomethane still releases GHGs into the atmosphere. But the combustion of biofuels is generally considered to be more climate friendly than burning fossil fuels because of the full life-cycle assessment of the process.

Biofuels generally refer to processed (often but not always) combustible liquid fuels derived from biomass (alcohols, diesel or oils). Biofuels are generally a refined, processed product (and therefore are more costly to produce than raw biomass), but can yield better energy efficiency when burned.

Two of the most significant reasons for widespread use of biomass and biofuels are the widespread availability (especially for biomass) and the convenience of using portable fuels that don’t have intermittency issues (like with wind and solar).

One of the significant downsides to both – but especially refined, non-algal biofuels is the land requirement to grow the feedstock – which is often quite significant.

Biomass: Biomass burning includes burning of biomass both for energy production and for forest or grassland clearing and scientists estimate that 90% of biomass burning is from human activity with only a small fraction of the total coming from natural (lightning-induced) causes. Biomass burning may constitute the burning of wood, food crops, grassy and woody plants, agricultural and forestry residues and other sources, such as dung. In many contexts in the global South, biomass burning is also associated with elevated levels of particulate air pollution and some adverse health consequences, particularly regarding respiratory and cardiovascular health. Some of the chemical pathways for these health effects are described in the figure and link below.

source: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.chemrestox.8b00318

Biomass burning from wildfires is proportionally more common in the middle to high latitudes, especially in the boreal forests. The summer of 2023, in particular was marked by an extraordinary wildfire season across many of the coniferous forests of the US and Canada.

For more information from NASA, consult https://eospso.nasa.gov/sites/default/files/publications/BiomassBurn_final_508_0.pdf

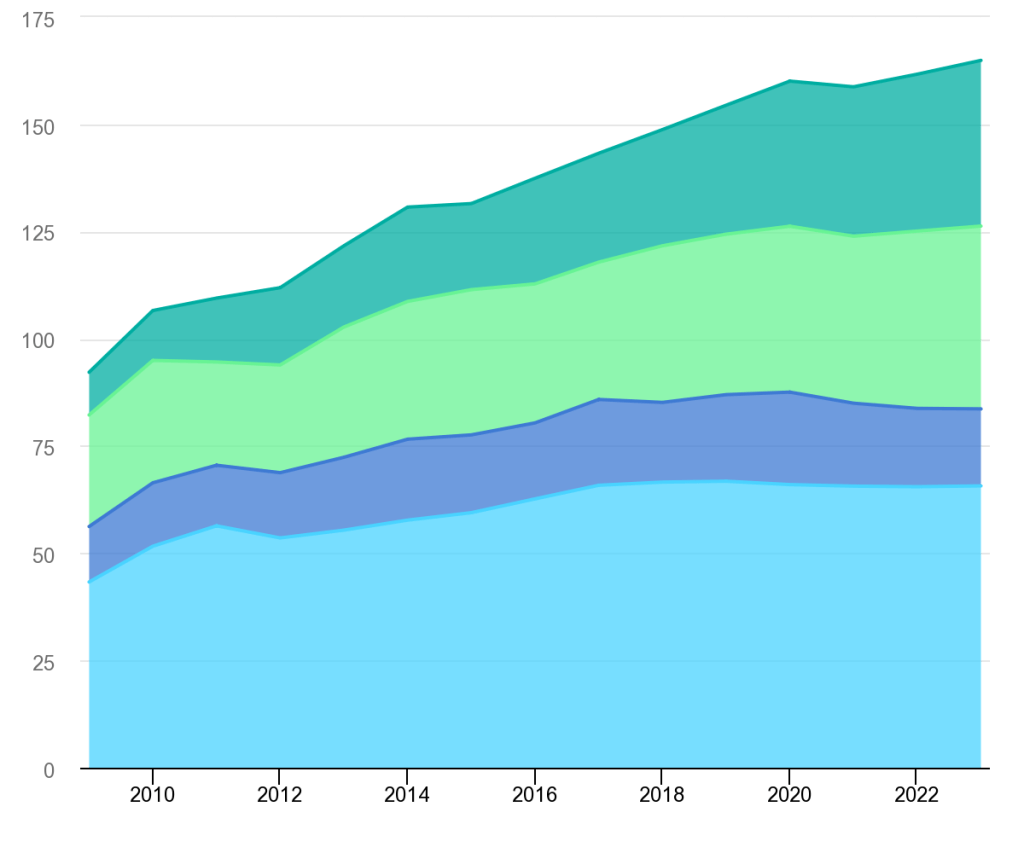

Conventional biofuels: Conventional biofuels involves the growth of crops that can be cultivated for their oils or starches which can be substituted for gasoline. Biofuels have been a rapidly growing resource, with now over 150 billion liters produced leading to something on the order of 1200 TWh or over 4000 petajoules of energy in 2023.

Biofuels can be made from a wide assortment of plants. In the US, starch-based corn ethanol is the most commonly used, whereas in Brazil, sugarcane-based ethanol is the dominant form of biofuel. Germany is a leader in biodiesel production. Waste cooking oil and vegetable oil can also be used as a substitute for gasoline. Other oil-based biofuels such as palm oil, rapeseed oil and jatropha can also be used as sources. Ethanol is more dominant than biodiesel. The recent biofuel production by country since 2009 is shown in the figure below.

source: https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/charts/global-conventional-biofuel-production-2011-2023

light blue = US, dark blue = EU, light green = Brazil, dark green = rest of the world

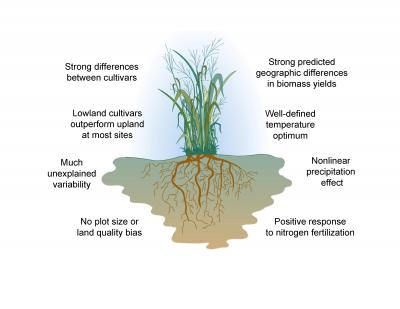

Cellulosic derivative material (using stems, leaves and other fibrous parts of plants) can have a better energy yield than starch based material when considering the full life cycle of biofuel production. These feedstocks also compete less with food crops, generally involve less maintenance and provide other soil-chemistry related benefits. However, the conversion of cellulosic material to ethanol faces some cost and technical challenges. Switchgrass is considered to be the potentially most widely viable source of cellulosic biofuels, but cost competition from other biofuels and from fossil fuels have made the economics largely untenable so far. More research and development is needed to bolster the technology required to produce switchgrass biofuels at industrial scale. Some of the complications are illustrated in the diagram below:

source: https://phys.org/news/2010-07-yield-switchgrass-biofuel-crop.html

Algal biofuels: The oily/lipid part of certain species of algae can be harvested to produce an assortment of liquid biofuels (including ethanol,

biodiesel, biobutanol, biogasoline, jet fuel, natural gas/methane (via pyrolysis and anaerobic digestion)). Algal biofuels have a number of advantages over conventional biofuels – including higher yields per unit of water and unit of area. As a consequence, there is much less land competition with agriculture. Algal biofuels can often be grown in a medium with reused or waste water and can therefore help to address water waste.

There are several architectures for plants to cultivate algae, including either vertical or horizontal tubes (closed photoreactors) or specialized ponds, such as the “raceway” style pond depicted below at UCSD.

source: https://today.ucsd.edu/story/uc_san_diegos_algae_biofuels_program_ranked_best_in_nation

Open ponds have a higher risk of contamination and offer the operators less control over environmental conditions, but are generally far less expensive and can generate a great deal more algae output than closed systems.

The closed photoreactor model tends to offer the operator more control, but tends to be considerably more expensive. Some images and description of advances in vertical photoreactor technology are described below.

source: https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlehtml/2022/se/d2se01345b

The significant impediment to wide-scale adoption of algal biofuels is the cost. The cost per unit of energy generated is still on the order of three times the cost per unit of energy for fossil fuels.

This being said, there are now demonstrations of the technical feasibility of biofuels as an energy source in the transportation sector with a number of cars that can run on biofuels and a number of Brazilian transportation vehicles that can run on sugarcane based ethanol. There have also been several long-haul (transAtlantic) flights that have been run partly on algal and other biofuels. Just this year, Virgin Atlantic and Boeing have had transAtlantic flights based on 100% sustainable aviation fuels (https://www.cnbc.com/2023/11/28/first-long-haul-flight-fully-powered-by-sustainable-aviation-fuel-takes-off.html).