Overview

For the majority of human history, food provision and production was the dominant economic activity of most people in most societies. This was certainly true of our early hominid ancestors and was certainly true of our hunter-gatherer ancestors who were early Homo Sapiens on the savannas of East Africa. Archaeological evidence suggested that fishing began at least 40,000 years ago. Around 12,000-8,000 years ago, in multiple early civilizations (China, Sumeria (modern Iraq), Egypt, Meso-America), agriculture began to develop and it has had a profoundly transformative impact on societies around the world. Domesticating and cultivating plants (and animals) for the purpose of food production in a specified place, enabled early agricultural societies to spend more time doing other things and to build more diverse economies and societies. While different farmers and livestock producers may have different specific goals for their personal farms, a goal shared by almost every farmer or livestock owner is to produce high quality food in abundance without excess unnecessary effort – in other words, to make the task of food production efficient and to more than meet the needs of the farmer’s own family. The success that many farmers have achieved in this goal has led many farmers to produce far more food than they consume, thereby enabling others in the same society to purchase food and spend their time and energy doing other tasks. Advances in farming have enabled societies around the world to develop a myriad of other industries, professions and technologies. In parallel, advances in fishing, harvesting edible marine and freshwater plants and aquaculture have also significantly increased food production from those sources.

Inter-connectedness

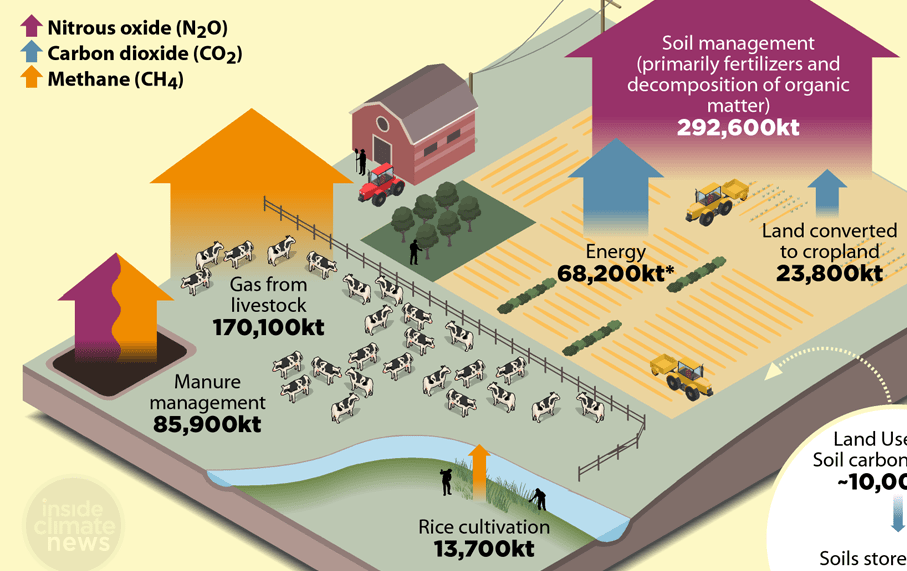

There are many ways in which food production both contributes to and is impacted by climate change. These issues are interwoven with other resource management challenges and with human health. Some of the interconnections are shown in the diagram below.

source: https://news.climate.columbia.edu/2020/02/18/focus-food-solve-climate-change/

Inequality

Our contemporary world is vastly unequal in its farming practices, production rates, resource consumption rates and levels of economic diversification. Modern agriculture both significantly contributes to and is significantly affected by climate change. A very small percentage of the population of affluent countries are involved in farming, livestock cultivation or fishing (in the US and France, it’s about 2% – in the UK, it’s about 1%). But many of the affluent countries produce an excess of food, relative to their own consumption (thereby becoming net exporters) and place a significant amount of land under cultivation. In poorer countries (many in Africa, Asia and Latin America), well over half of the population (and sometimes more than 80%) are involved with primary food production. However, most of this food production is done by small holder farmers with limited inputs who are just trying to subsist (grow enough food to feed their own families). Often, food security is much more constrained in developing countries. Agriculture in the affluent world is supported significantly by highly mechanized machinery, fertilizers and in many cases, extensive irrigation. In many affluent countries, there is also considerable financial support for agriculture in the form of government subsidies and public and/or private insurance. These protections insulate farmers against some of the costs and shocks inherent to farming. Much of the food produced in affluent countries is produced by large companies that own huge tracts of land and put much of it under intense cultivation (often for just a handful of crops).

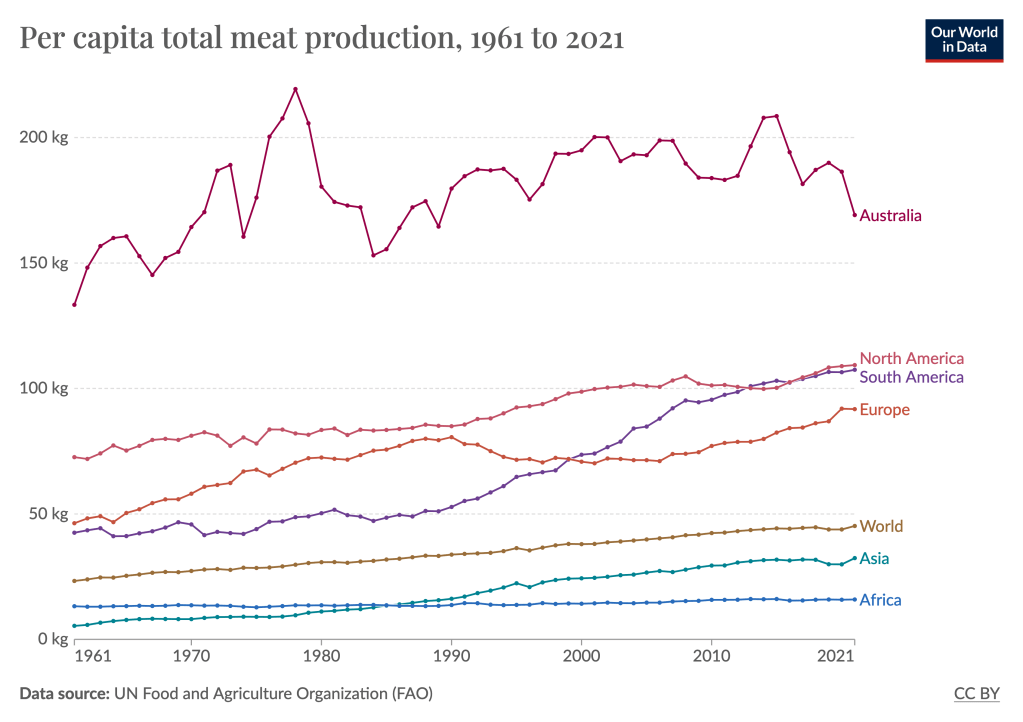

In contrast, in the developing world, such large businesses, technologies, inputs and financial protections are rare – leading many farmers in the developing world to be far more exposed to the challenges of nutrient depletion, price shocks for basic inputs and weather/climate related risks. Likewise, most commercial fishing in affluent countries is carried out by large scale companies using large trawl nets that can be very damaging to the ecosystem, whereas most fishing done in developing countries is small-scale artisanal fishing carried out by smaller boats with either smaller nets or lines. The figures below show per capita cereal and meat production for the globe and by continent from 1961-2021. The differences can be largely explained by the differences in overall income, but local factors also play a significant role. Some countries that are relatively affluent have limited area for cultivation or produce more fruits, nuts and other non-cereal crops than cereal crops and some relatively affluent countries have limited land for livestock cultivation and less of a culture of consuming meat than others.

source: https://ourworldindata.org/agricultural-production

A global ranking of the fraction of the workforce engaged in agriculture/food production can be found at this link: https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/rankings/employment_in_agriculture/.

Hunger and obesity

As a consequence of this inequality in production and other issues associated with markets, trade, price volatility and international and sub-national politics, there are also profound inequalities in food security and availability. As mentioned on the public health page, there are 9 million deaths per year from hunger or malnutrition related issues (out of about 60 million deaths per year worldwide). Almost a billion people lack access to enough food to meet their caloric needs. On the other end of the spectrum, over a billion people worldwide are now considered obese (with many more considered overweight) and many countries around the world can provide their citizens ample access to food. However, when this food is abundant but poorly regulated, loaded with addictive elements, highly processed, calorie rich but micro-nutrient poor, over-consumption and obesity become greater risks. There are 5 million deaths per year directly from obesity and many more from related cardiovascular conditions (high blood pressure, heart disease, diabetes, etc.) (World Health Organization).

Contributions to Climate Change

Agriculture and livestock production contribute to climate change through multiple pathways. Tilling of soil releases carbon stored in the soil. Farm animals release methane naturally. Significant energy is required to conduct mechanized harvesting, make and apply fertilizers and to conduct large scale irrigation operations. There are also significant energy costs associated with transporting farm products to market. Intensive monoculture can also deplete the soil’s fertility, nutrients and capacity to act as a carbon sink over time. Many of these pathways are illustrated by the diagram below.

Animal cultivation is particularly damaging to the environment because it takes so many resources to raise a farm animal (especially large cattle) to the age when it is appropriate to slaughter. As a general rule in biology, higher trophic levels require more energy from lower down the food chain. Diets lower in meat, and especially lower in red meat are generally more eco-conscious. Commercial fishing has also been very environmentally damaging – both through the direct impact on fish populations (many of which are now at 10% their pre-Industrial Revolution population) and through climate change (both by the energy consumption involved in fishing and transport and by the disturbance of deep carbon stores by trawling nets (https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2023.1125137/full).

Vulnerabilities to Climate Change

But in addition to the many ways in which agricultural, livestock cultivation and fishing practices have contributed to climate change, these activities are also very vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. The success or failure of many crops grown by farmers around the world depends intimately on the nutrients in the soil and the pattern of water availability and temperature stress the crops face. The yield of many crops is intimately dependent on not just the total seasonal amount of rainfall, but the timing of rainfall within the season (date of onset, frequency and severity of dry spells) and on extremes of temperature. In affluent countries, heavy use of fertilizers and irrigation generally helps to offset some of the vulnerability that would come from natural exposure to drought and soil degradation. Such inputs are often energy intensive, costly and can lead to other down-stream environmental problems (dead-zone anoxic conditions in downstream water bodies, ever sinking water levels in heavily tapped aquifers). In poorer countries, irrigation, fertilizers and certainly advanced, mechanized farming equipment are far less available – so the dependence on natural rainfall and vulnerability to climate extremes is greater.

Higher temperatures lead to more evapotranspiration and water stress. More erratic rainfall also leads to more water stress. While seasons with moderately above average rainfall can be beneficial to crop yields if that rainfall is well distributed, severe storms can waterlog soils, become breeding grounds for agricultural (and human infecting) pests and diseases and can strip away vital nutrients.

Pastoral communities also depend on climate for forage/pasture land. If and when rainfall patterns grow more erratic, finding appropriate pasture land for roaming livestock becomes a greater challenge and may bring pastoralists into increasing resource competition and conflict with other pastoralists, farmers and other groups.

Fisheries are also intimately dependent on climate – ocean temperatures and acidity levels have a critical role to play in marine ecosystem health and oceanic dynamics play a vital role in the amount of nutrients available to different fish species. Cool, upwelling water is often more nutrient rich than warmer surface water and as the climate warms, the rate of upwelling may decline. The diagram below from the Climate Change Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS) initiative of the Consultative Group for International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) illustrates some of the key adaptations that can make food production more resilient to climate stresses.

source: https://ccafs.cgiar.org/news/climate-change-and-farming-what-you-need-know-about-ipcc-report

In addition to direct impacts on food production, climate risks may also have impacts on the price of fuel, transport and other aspects of the supply chain of food – which may challenge the livelihoods of those who produce our food and many communities around the world. The diagram below from the UK Met Office illustrates the scale of food insecurity around the world and it’s connection to climate risks. The height of the person figures indicate the percentage of the nation’s population that is undernourished – with the taller darker figures indicating a higher percentage. The colorscale indicates the hunger and climate vulnerability index with the dark red indicating the highest vulnerability and yellow indicating the lowest.

source: https://awellfedworld.org/food-insecurity-climate-change/

Farming plants (grains, nuts, fruits and vegetables)

All plants need appropriate conditions of sunshine, nutrients, soil characteristics (including pH), water and temperature in order to grow in a healthy, productive way. Drought tends to make soil more acidic, while flooding tends to make soil more alkaline. While most plants can tolerate some variability in pH, protracted droughts or flooding can cause direct damage and can compromise soil features enough to reduce yields.

Soils naturally benefit from some periods of laying fallow (not being cultivated at all), crop rotation (changing which crops are grown in an area from year to year), and intercropping (planting multiple cultivars next to each other). Some smallholder and organic farmers in affluent countries regularly engage these practices. Many smallholder farmers in developing countries engage in these practices as well. The photos below is of an intercropped organic farm.

source: https://agrimate.org/how-to-do-intercropping-in-organic-agriculture/

However, large, industrial scale agricultural operations that produce the bulk of the food in the affluent world usually do not consider such practices economical for their interests. In other words, if the goal is continuous large scale production, allowing fallow seasons is perceived as a lost opportunity, and intercropping and crop rotation are more complicated to execute on an industrial scale – it’s much easier to plant a large field with one type of crop with large scale machinery. Much of the large, industrial scale farming in the affluent world is in the form of monoculture (i.e. huge fields of one single crop). The image below is of a monocropped field.

source: https://morningchores.com/monoculture/

Monocropping can lead to soil degradation and nutrient depletion and often requires more water and more nutrient inputs than other forms of farming – but it does tend to lead to greater efficiency of production by unit of land – at least in the short run. The nutrient depletion issue is often “solved” by the heavy application of fertilizers and irrigation. But the heavy application of fertilizers has downstream consequences in water pollution. Because of the scale of fertilizer application in the farming regions of the US, there are often heavy nutrient loads in the waters of the lower Mississippi river that can lead to harmful algal blooms in the Gulf of Mexico. These, in turn deprive much of the subsurface water of oxygen, leading to a hypoxic “dead zone” in the Gulf of Mexico off the shore of Louisiana. This is depicted in the map below.

source: https://www.noaa.gov/news-release/larger-than-average-gulf-of-mexico-dead-zone-measured

In the affluent world (particularly in the US), much of the plant matter that is produced is not intended for human consumption, but rather for animal feed. It’s estimated that in the US only about 27% of crops are grown for human consumption, while almost 70% are grown for animal feed and the balance are grown as biofuels (source: https://thehumaneleague.org/article/animal-feed).

The norms in the developing world are very different. Most farmers operate a small and subsistence scale. Use of fertilizers, mechanized farm equipment and irrigation is limited and many small-holder farmers in the developing world are very directly vulnerable to changes in soil fertility or water stress.

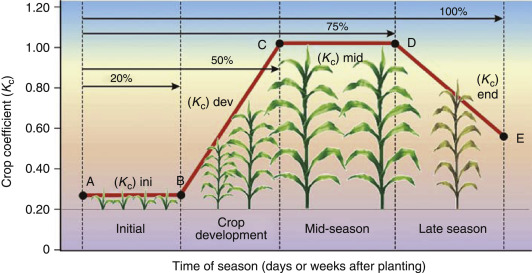

All types of crops have specific water needs at different stages of their growth and development. Broadly speaking, the stages of crop growth are germination, leaf development, further growth of side shoots and size, flowering, fruit or seed development and ripening and senesence. These can also be thought of as the initial, crop development, mid season and late season stages. While the overall water requirement early in a crop’s life is typically less than later on, droughts, frosts or exceptional heat waves early in a crop’s development can be especially damaging. The diagram below shows a generic crop coefficient (Kc) curve as a function of the period of the season. The Kc value is the ratio of the actual crop evapotranspiration to the reference crop evapotranspiration.

source: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/earth-and-planetary-sciences/crop-coefficient

In order for a plant to avoid being in water stress, the amount of rainfall and soil moisture it can access on any given day must exceed the evapotranspiration. That need is more limited early in the season than at full maturity, as indicated by the curve above. Often, agricultural scientists will study water balance models, such as the Water Requirement Satisfaction Index (WRSI) which calculates a running total of the accumulated water stress over the season on the basis of the daily rainfall input, the daily evapotranspiration rates and the Kc curves.

In agricultural contexts where irrigation may be limited, there may not be much recourse to drought after planting (but some skillful climate prediction may help a farmer decide whether or not to buy a drought resistant strain of a common crop or whether to plant more drought resistant cultivar that season). But in contexts where irrigation is possible, farmers may use irrigation to address the water needs of their crops. The big challenges with irrigation, of course, are efficiency and sustainability. Flood irrigation is often very wasteful because it leads to much of the water being evaporated without getting to the plants. Spray or mist irrigation can be somewhat better, but still often leads to high evaporation rates. Drip irrigation and pipe irrigation, where water is applied in small quantities directly to the plants roots is often much more efficient in terms of minimizing evaporation, but often costs more to establish and maintain.

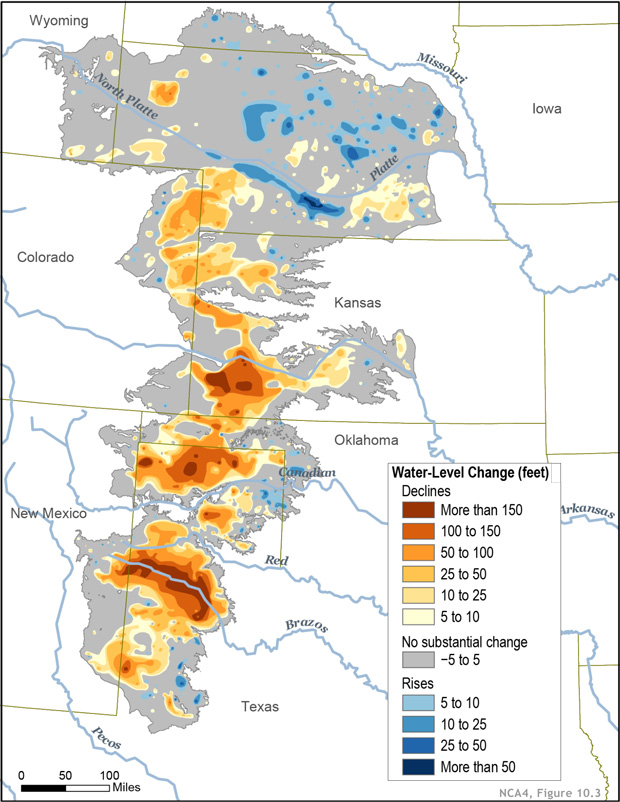

Many farmers and many government policies around the world effectively treat irrigation as a limitless resource because of the potential short benefit to the farmer. However, this tends to lead to unsustainable practices. A great deal of irrigation in the American midwest and west, in India’s drier northwest region and in many arid or semi-arid regions around the world involves tapping into ground water resources at unsustainable rates. The map below shows the level of depletion of the massive multi-state Ogallala aquifer in the western part of the US Great Plains. This subterranean resource has been exploited for years at rates that are unsustainable.

Another issue with plant agriculture in the affluent world is that there are sometimes perverse incentives to grow crops that are poorly suited to the climate and environment. For example in the US, a great deal of agricultural produce is grown in California’s Central and Imperial valleys. Both environments have abundant sunshine and fairly fertile soil, but tend to get extremely hot in the summer and have very limited rainfall. Yet many of the crops grown in this region demand a great deal of water – and thus a great deal of irrigation.

Livestock Cultivation (Meat, Eggs, Dairy)

All farm animals need adequate (and sanitary) food and water to survive. Farm animals also benefit greatly from having adequate space to move around in and fresh air to breathe in order to be healthy during their lives before slaughter.

Unfortunately, given the very large (and growing) global demand for meat, many livestock operations in the affluent world (particularly in the US) are in the form of confined animal feeding operations (CAFOs). Although CAFO-like facilities have also been developed in Europe, China and Australia. These operations pack thousands of animals into very small spaces and often severely restrict movement of animals. These operations provide the basic food and water the animals need to eat and grow, but dealing with waste and disease in such confined quarters is a constant challenge. Often, the “feed” that is given to animals in CAFOs is not their natural diet (which would ordinarily be grass), but rather a type of corn or soybean residue – because it is cheap to procure and tends to lead to many animals “fattening up” more quickly. Because of the limitations of movement and the sanitary and overcrowding issues, the quality of life that many farm animals experience in CAFOs is quite poor and there are often major problems with environmental pollution in nearby water bodies. In CAFOs, there is also a tendency by farmers to over-medicate their animals…because disease risk is very high in such settings. Unfortunately, this can sometimes lead to the development of medication resistant bacteria and viruses. In addition, when humans ingest the meat from animals that have been cultivated with high loads of antibiotics, it affects our own immune system and helps to breed new antibiotic resist strains of common pathogens and some research indicates that ingesting such meat may have other damaging health impacts in terms of inflammation, hormonal changes and elevating the risks of certain cancers.

source: https://sevensons.net/what-is-cafo – image from a chicken CAFO

source: https://sentientmedia.org/what-is-a-cafo/

For large scale egg and milk/cheese production, often chickens and cows that are being cultivated for their eggs and dairy are also held in high density environments and forced to produce eggs and milk much more frequently than would normally occur.

While large, mega-businesses may be responsible for much of the volume of meat, dairy and eggs produced in affluent countries, there is definitely a smaller vocal movement to cultivate animals in a more sustainable and humane manner – ensuring no cages, freedom to roam over a large area and feeding the animals grass, rather than corn and/or hay. This approach requires more land per animal and a more “hands off” approach, but leads to healthier lives for the farm animals and for the humans who eat their meat, eggs and cheese or drink their milk. This is the norm on many more sustainable farms and ranches. While there are many people involved with solely producing meat or dairy products in the affluent world, they tend to live on ranches or farms, rather than being nomadic (as is often the case the developing world). Below is a picture of cows grazing on an organic farm in Canada

source: https://bradnerfarms.com/organic-beef/

Livestock cultivation in the developing world is often much different. Many poorer farmers in developing countries cannot afford large cattle and cultivate primarily smaller animals: goats, chickens, sometimes sheep – and the animals’ food source is almost always the natural vegetation on the ground. This being said, there are still many farmers in the developing world who do raise cows and other large cattle (eg. water buffalo). But CAFOs are not a norm in most developing countries. Many farmers in developing countries raise a mix of animals and plant crops. But there is also a large population of pastoralists in the developing world who cultivate only animals but migrate continuously in search of good pasture for their flock. They often live in the most arid and semi-arid regions (as plant crops may not survive in extremely dry conditions – but certain cattle species can survive on limited scrub vegetation). Sometimes, especially during drought conditions, limited water resources will lead pastoral populations to come into resource competition or conflict with settled farmers. The image below depicts pastoralists in the arid regions of Kenya.

Fisheries and Seafood

All fish need healthy water (in terms of pH, salinity, temperature, oxygen and pollution) in order to survive. As human’s impact on the environment continues, all of these factors are threatened – the world ocean is filling with micro and macroplastics, becoming more acidic, temperatures are rising, and more of the world’s ocean is becoming depleted in oxygen. As with farming plants and animals on land, the majority of the world’s wild caught seafood is acquired by large industrial-scale fishing vessels which often conduct fishing by huge trawl nets. While they are the most economical means of bringing in huge hauls of fish, these huge trawl nets are profoundly destructive to oceanic environments and ecosystems. They ensnare enormous number of animals of species that are not the intended catch (called bycatch – it’s estimated that something like 20% of the haul of bottom trawl nets is bycatch) and they do a great deal to disturb the ocean floor. Some recent research suggests that trawl nets stir up a great deal of stored carbon in sediments at the bottom of the ocean which are then entrained into the mixed layer and are released into the atmosphere (https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2023.1125137/full). A schematic image of how bottom trawling works is shown below.

The graph below shows the scale of industrial, small scale (artisanal), recreational, and subsistence fishing and discards (bycatch) from 1950 to 2010. While the end of this graph is a bit dated, the trend of the majority of fish being caught in large industrial operations continues.

source: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/global-fishery-catch-by-sector

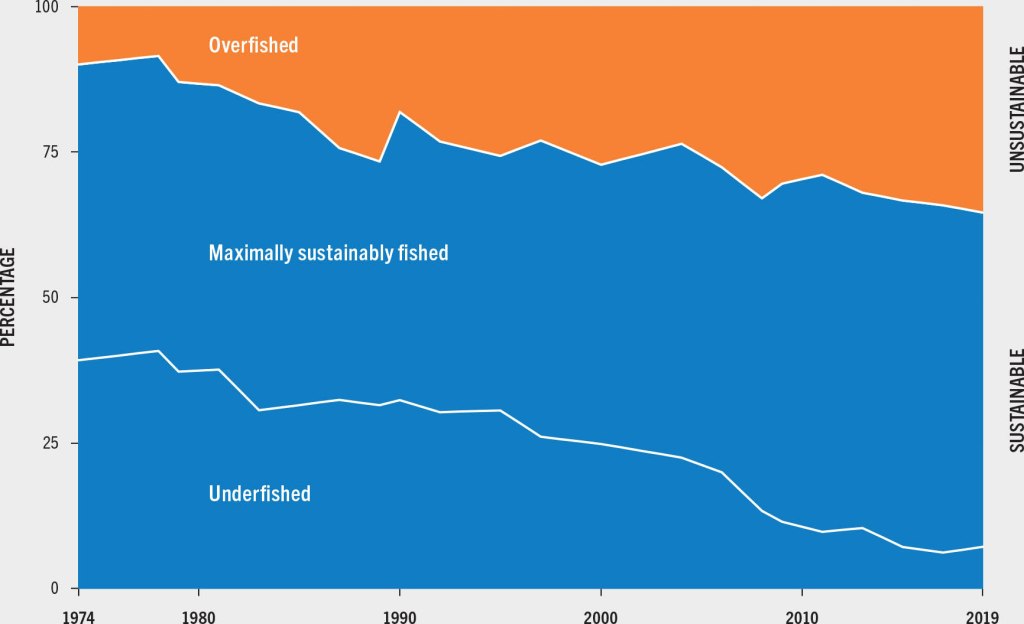

While many fish stocks are overfished, some regulations and practices have kept catch rates in line with sustainability concerns. Still, over time, the fraction of fish stocks that have been overfished has continued to rise as the graphic below illustrates.

source: https://www.fao.org/3/cc0461en/online/sofia/2022/status-of-fishery-resources.html

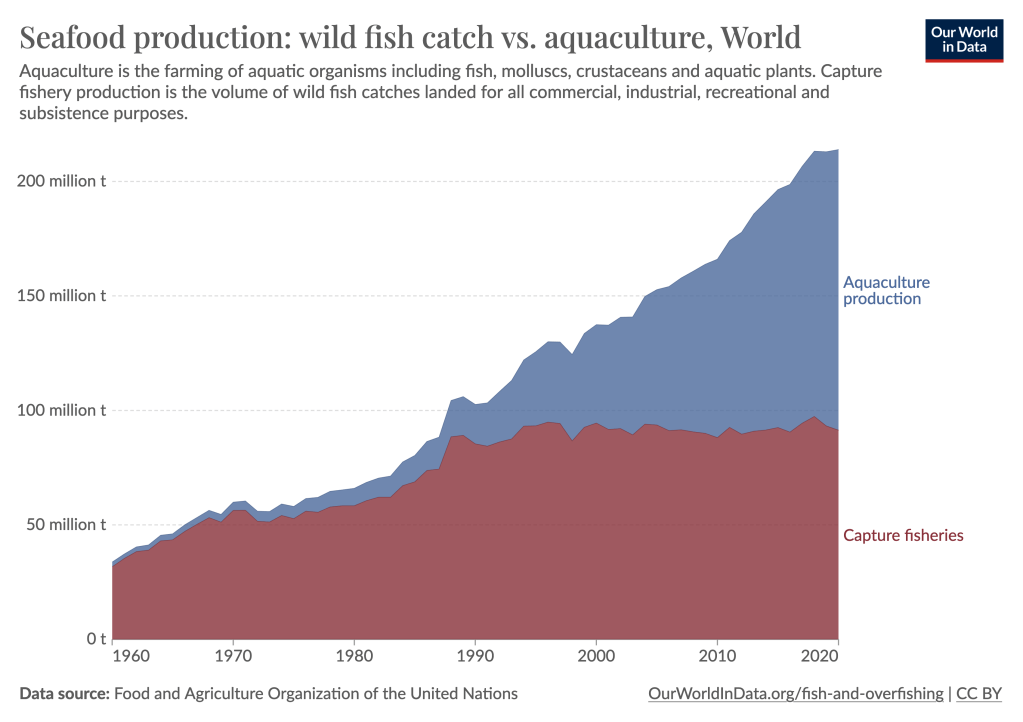

Since the 1990s, the (relatively) new approach to fishing (of aquaculture) has grown significantly and is now responsible for almost half of all seafood/fish production. This is shown in the graphic below. A significant fraction of this aquaculture takes place in inland waters – because managing aquaculture operations far from shore in marine environments is more complex and costly.

source: https://ourworldindata.org/fish-and-overfishing

In addition to overfishing, there is a significant challenge to global fisheries in that the world’s oceans are getting warmer, more acidic, more polluted and more hypoxic. The warming trend may also have the effect of limiting the upwelling rate of cold nutrient and oxygen rich water to the surface in some areas.

Issues with Inter-connectedness

Our global food system is also a highly interconnected system, which enables global trade of foods, spices, ingredients, etc., but can also produce significant vulnerabilities. For many countries and regions that do not produce certain key staple foods in large quantities within their own borders, they must import the balance to meet their demand. When there are supply disruptions for any reason (climatic or geopolitical), this can lead to price spikes that can then render many people food insecure and cause inflation. Russia’s war against the Ukraine has slowed the shipment of Ukrainian food to the rest of the world. This has had significant impacts on the acquisition of staple crops in much the developing world which depends on the Ukraine for such resources. Militant attacks by Yemeni Houthi rebels in the Red Sea have also disrupted supply chains that pass through the Suez canal.

There is also published literature suggesting that climate variability may adversely impact multiple breadbasket regions for staple crops at the same time (Anderson et al. 2023).

One of the major projects underway to understand the linkages between different climate futures and the potential implications for Agriculture is the Agricultural Model Intercomparison Project (AGMIP)

An initiative designed to address yield gaps created by water and nutrient deficiencies is the Global Yield Gap Atlas (GYGA).