Overview: Financial institutions and insurance companies are very concerned about climate change because of the climate related financial risks they face. But they also have an important role to play in financing disaster recovery and offering means of financial adaptation and support to those affected by climate impacts. The other side of the corporate response to climate change has to do with decarbonization and sustainability, which is mentioned on another page. Banks and financial consulting firms are concerned largely with costs associated directly with climate-related physical damage, the risk of default on loans by individual and corporate borrowers, and financial exposure of investment portfolios to sustained climate related physical and transition risks.

Physical Risks: Physical risks refer to the direct economic impact of adverse climate conditions on people, properties, etc.. Generally speaking, both in the US and abroad, because of population increases and the increase of valuable infrastructure at risk, physical risks have increased significantly over time, even independent of climate change. The changing climate then also adds additional risk through geophysical exposure. The economic impact of physical risks on individuals, companies and communities can have long-lived implications for their financial position and ability to pay standard costs of living (taxes, mortgage, rental fees, etc.). Physical risk impacts may also introduce significant new costs into an individual’s life or a company’s business operations – through necessary repairs to a damaged building, etc., which may have knock on financial consequences. There can also be differentiated short term and long term financial consequences (eg. some research on the impact of hurricanes on real estate prices in the US indicates that shortly after a hurricane, the value of homes in an affected region (that aren’t badly damaged) tend to increase significantly, even though serious hurricane damage may be a long term economic depressant to the region).

Transition Risks: Transition risks refer to the financial risks associated with the “transition” to a lower carbon future. Financial firms are interested in turning a profit, but do not want to be on the losing side of a policy transition with a lot of stranded investment assets. Stranded assets might include investments in fossil fuels that fall out of favor or become non competitive in an evolving regulatory landscape, bad bets on specific green energy technologies. Transition risks are generally much more difficult to quantify and involve more uncertainty because of uncertainties in technology, markets and the policy/regulatory landscape.

Insurance: Insurance companies can write a number of types of policies, including parametric or indexed policies that address climate risks but have a profit driven motive to act a bit conservative regarding their own portfolios’ climate risk exposure. Insurance companies that insure properties and businesses prone to climate related risks are particularly interested in understanding the recurrence interval of certain types of events and the probability of a run of bad years that trigger policy payouts in quick succession, and have often responded to increasing climate risks by withdrawing coverage from certain risk prone areas (NY Times article).

For any type of insurance regarding climate risk, the actuarially “fair” premium for a policy written to insure against such a risk is the probability of occurrence of the event that would trigger the payout multiplied by the size of the payout (insured liability). Real world premiums are always a bit higher because of the transaction and labor costs of developing the policies, the uncertainty risks the insurance company faces and the need for insurance companies to turn a profit.

Globally, both insured and uninsured losses have increased substantially over the last 40 years or so. This is shown by the figure below from Swiss Re. A large part of that increase in both insured and uninsured losses is a function of more value at risk as a function of expanding human population and infrastructure. But some is attributable to the increased severity of individual events. While not all of this increase is attributable to climate related factors, climate factors are a substantial driver of the highest impact years (2005 being marked by multiple devastating hurricanes in the US, 2011 being marked by the devastating Fukushima earthquake and tsunami in Japan and flooding in Thailand and 2017 also being marked by a number of extreme hurricanes in the US and Caribbean).

Traditional Loss Based Property/Casualty Insurance: Traditional loss-based insurance for property damage or personal injury/casualty contracts require the person seeking a payout to file a claim and for the losses to be verified before the insurance company pays the claim. This structure of contract gives the insurance company a fair amount of control and can more closely align the payout with a demonstrated loss and is often used to address certain types of weather damage in the affluent world. However, when a disaster affected region is remote or difficult to access or losses are difficult to estimate/quantify, this model of insurance contract may prove challenging for addressing the needs of the affected. Such challenges are often at play in the developing world, where a traditional loss/verification framework for insurance payout is largely practically unfeasible.

Reinsurance: Reinsurance companies act as the “insurers of last resort” for the rest of the insurance market, providing policies for other smaller insurance companies for their risk of default. Many of the large reinsurance companies are based in Europe and take a pretty global view of climate related risks and carefully monitor evolving risks.

Catastrophe Bonds: Catastrophe bonds are another way for investors and insurers to work together to manage climate risks. An investor who buys a catastrophe bond is taking a bet that the specified catastrophe type will not occur in the designated region in the designated time frame. If this bet proves correct, the investor is returned the principle + a relatively high interest rate at the end of the bond period. If this bet proves incorrect, the investor loses the investment and the insurance company that has sold the catastrophe bond can use the premium money as another revenue stream to address its obligated payouts.

Weather Derivatives: There are several possible contract structures and designs (and markets) for weather derivatives. But basically, the seller of a weather derivative assumes a weather related financial risk in exchange for a premium payment up front from the buyer. If no weather/climate disaster occurs in the specified time window, the seller makes the profit of the premium. If the disaster does occur, the seller must return the premium + interest to the buyer.

Index Insurance: The idea behind index insurance is to design an insurance product that pays out when a geophysical index reaches a specified critical threshold that is correlated with an economic or livelihood risk. Because an index insurance policy’s payout is tied to the index and not explicitly to verified losses, it may be imperfect, but it is an approach to insurance design that is more scalable and deployable in challenging contexts like the global South.

Potential indices for index insurance include; rainfall (gauge or satellite), streamflow, reservoir level, temperature, vegetation greenness (NDVI), water requirement satisfaction index (WRSI) etc..

Some of the potential advantages of index insurance include a faster payout than would be possible with a loss-verification model, no or reduced moral hazard (no incentive to commit insurance fraud), and lower transaction costs (relative to loss-verification insurance.

Some of the disadvantages/limitations are that index insurance contracts only address a specific type of risk, there is the issue of basis risk (large impact, but no payout because the index didn’t reach the critical threshold), and default risk (not enough premium to cover payout costs).

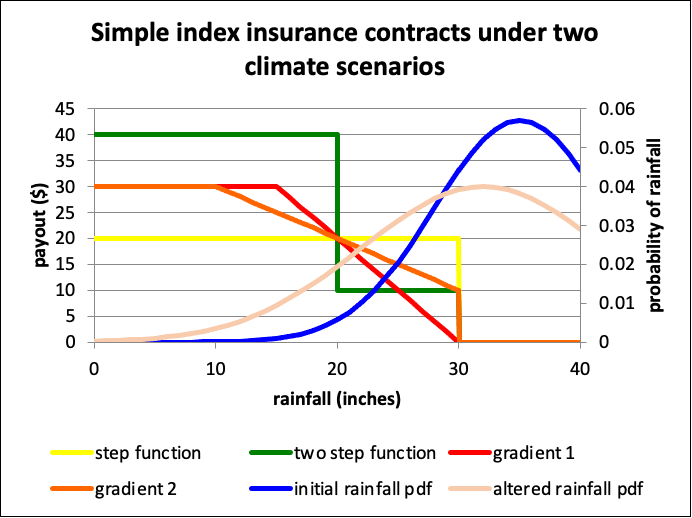

Index insurance has potential as an adaptation tool in the developing world where insurance infrastructure is limited or non-existent. It can enable farmers to take riskier, but potentially higher yield decisions that can alleviate poverty in the long run. Index insurance contracts can be designed with different possible payout functions. Four potential payout functions are depicted in the graphic below for drought/low rainfall index insurance involving an initial climate (with a wetter mean and smaller standard deviation) and an altered climate (with a drier mean and a larger standard deviation).

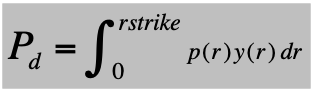

For a rainfall-based drought contract, the actuarially fair premium would determined by the equation below, where p(r) is the probability of rainfall amount r, y(r) is the payout as a function of rainfall r and rstrike is the threshold or strike level at which the contract first pays out. The integration interval is bounded by 0 (minimum possible rainfall) and rstrike because for all larger rainfall levels, there is no payout.

Using the equation above with graphic above, the actuarially fair premiums are as follows:

| Price | Step | 2 step | Gradient 1 | Gradient 2 |

| Initial (wetter) climate | $4.76 | $2.86 | $1.72 | $3.24 |

| Altered (drier) climate | $8.41 | $7.66 | $5.40 | $7.03 |

Additional considerations in insurance pricing include the risk of default – or the risk of a large number of payout events in a short period of time. This can often be modeled using a Monte Carlo approach like the one described in the coding pages.

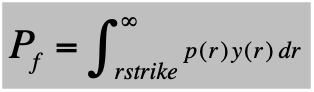

For a rainfall-based flood or excess rainfall contract, the actuarially fair premium would determined by the equation below, where p(r) is the probability of rainfall amount r, y(r) is the payout as a function of rainfall r and rstrike is the threshold or strike level at which the contract first pays out. The integration interval has a lower bound of rstrike because for all smaller rainfall levels, there is no payout. Extremely high levels of rainfall may be very rare, but they are not physically impossible. But in order to design a contract that is bounded, it is sensible to put a maximum cap on a flood index insurance contract (i.e. not have an unbounded gradient payout function).