Climate has a number of well-documented direct and some indirect impacts on human health, as well as having important impacts on ecosystems and animal and plant health. Holistically, many of these health impacts are summarized in the schematic graphic below from the US Center for Disease Control (CDC), which connects the climate impact to environmental impacts to human health impacts.

Source: https://www.cdc.gov/climateandhealth/effects/default.htm

Heat

Higher temperatures, particularly during summer heat waves have been shown to dramatically increase the risk of direct heat related health conditions (heat cramps, exhaustion and stroke, dehydration) and associated mortality. Interestingly, the research in this area tends to show that while acute episodes of heat cramps and stroke are most common during peak heat hours during the day, more prolonged and serious health impacts arise from sustained very nighttime temperatures (when coupled with no air conditioning). As with many health conditions, these risks are particularly pronounced for the elderly, very young children and pregnant women. Excessive heat stress is also an exacerbating factor to many cardiovascular and respiratory conditions. Severe heat stress is also particularly pronounced in urban environments – where the urban heat island effect can often raise the ambient ground level temperature in a major city by up to 5C over the ambient temperature in surrounding suburbs. This heat intensification in urban environments, coupled with other local sources of air pollution – including particulates, volatile organic compounds and elevated levels of low-level ozone can be especially damaging to the health of people already suffering with chronic respiratory or cardiovascular issues. This effect is observed quite often in “developed world” cities (eg. the Paris heat wave of 2003), as well as “developing world cities” (numerous unrelenting heat waves in Africa, the middle East and South Asia). It’s somewhat difficult to quantify the total death toll from extreme heat because many people who die from heat related exposure have other underlying risk factors that ultimately claim their lives. But individual severe heat waves covering a few hundred or thousand square miles and lasting for a few weeks have been known to lead to tens of thousands of deaths, as calculated from “excess mortality” statistics.

High temperatures alone are not the sole culprit…when humidity is very high, a lower ambient temperature is needed to produce the same wet bulb or heat index temperature. In very high humidity environments, the body’s ability to cool itself through sweating is limited. When the wet bulb temperature rises above the temperature of the human body (37C or 98.6F), the body is no longer able to cool itself via sweating at all. A number of studies show that there is a significant likelihood that hundreds of millions of people (particularly in the Middle East, Northern and SubSaharan Africa, parts of the Americas, the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia) may face these kinds of temperatures and heat indices on a much more frequent basis, unless significant efforts are taken to limit GHG emissions and cool the planet. For example, one recent study found that climate change has made devastating early season (March and April) heat 30 waves times more likely in India and Pakistan than would have been the case without human climate change

The image on the left shows the raw average temperature in March-April of 2022 and the image on the right shows the anomaly relative to the long term baseline (1979-2022).

Drought

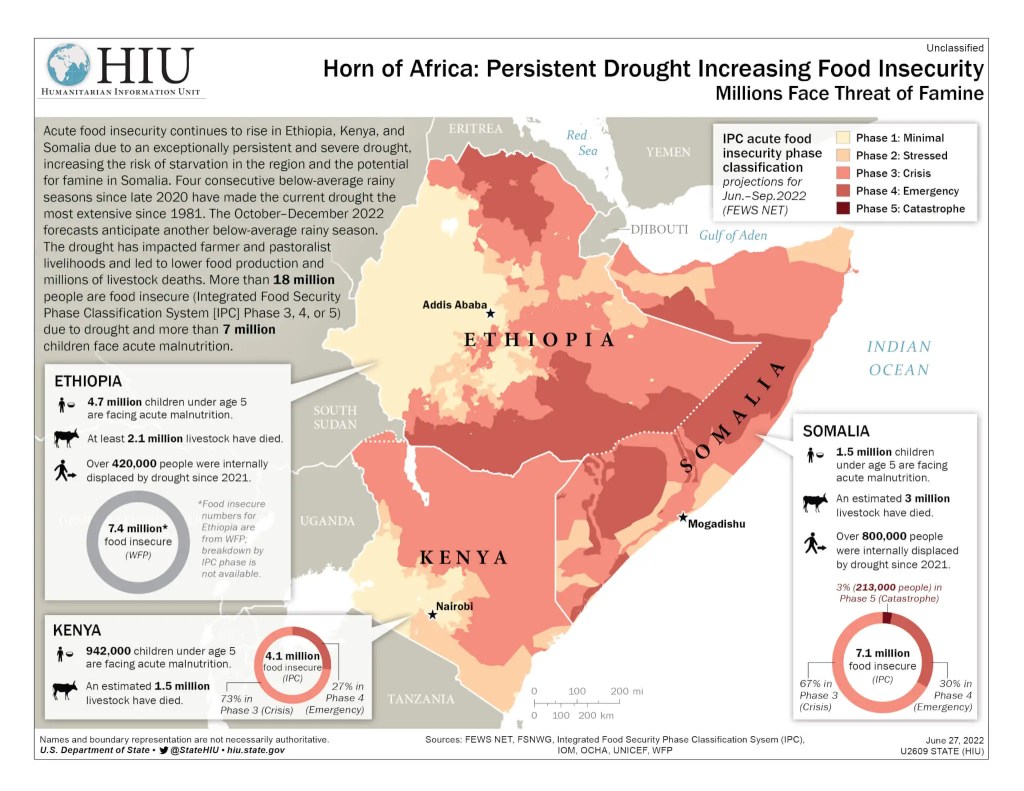

Drought and the often associated dehydration and food insecurity that accompanies severe droughts can considerably weaken the human immune system and can make the human body more vulnerable to many other diseases. Famines are marked by widespread extreme hunger and malnutrition and can lead to specific adverse health impacts like marasmus (stunting and wasting malnutrition) and kwashiorkor (severe protein malnutrition marked by emaciated appearance with abdominal bloating due to weakened abdominal muscles). Globally, hunger, malnutrition and related conditions lead to about 9 million deaths per year (for point of comparison, in recent years the total global death rate from all causes was about 60 million deaths). While not all famines are explicitly linked to drought, many are. Tragically, about a third of these deaths are for young children. Globally, there is more than enough food to meet the caloric needs of every person on the planet. Hunger and famine is almost always a confluence of natural conditions, power imbalance, weak infrastructure, weak or compromised institutions and corruption.

https://umcmission.org/story/responding-to-drought-and-famine-in-the-horn-of-africa/

In developing countries, many epidemic conditions are more pronounced after severe droughts – in large part because of how drought and food insecurity can weaken the immune system.

However, drought conditions, especially coupled with windy, sandy/dusty conditions in areas like the arid Sahel of Africa can increase vulnerability to bacterial meningitis. The sandy, dusty conditions help enable the bacteria to spread from the nose and throat into the lungs. Consequently, in the “meningitis belt” of subtropical Africa, the peak incidence of meningitis tends to be before the onset of the rainy season and tends to be particularly pronounced after unusually dry rainy seasons. This relationship is explained further in the video clip below in a video segment by Dr. Judy Omumbo.

source: https://www.climate.gov/news-features/videos/climate-and-meningitis-africa

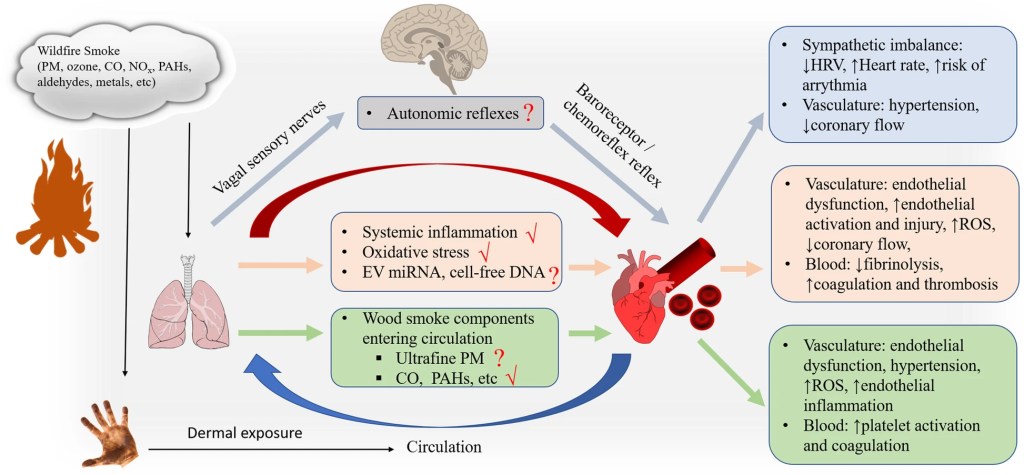

Heat and drought induced wildfires can also lead to significant public health impacts on cardiovascular and respiratory systems – as recent severe wildfire seasons in many regions have clearly demonstrated. Wildfire smoke can create systemic inflammation, heighten asthma risk, complicate cardiovascular diseases and strain respiratory systems and can have other impacts on blood chemistry and the nervous system as the diagram below illustrates.

source: https://particleandfibretoxicology.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12989-020-00394-8/figures/2 (Chen et al. 2021)

Severe storms

Severe rain and wind storms (especially, but not limited to tropical cyclones) can compromise health through multiple pathways. Cyclones have the added impact of storm surge near their landfall, but wind and rain damage are a common feature with other types of severe storms (eg., tornadoes, derechos, severe thunderstorms). With major severe storms, there are often many people directly killed, injured or drowned in the damage and many more injured by damaged structures, falling trees, etc.. For thunderstorms, lightning strikes do sometimes kill or injure people and can damage infrastructure. In colder climates, severe winter storms (particularly those with a lot of ice) can have significant impacts on power, heating and transit infrastructure and lead to many road accidents and associated injuries and fatalities. Death tolls and injury tolls from hurricanes and other severe storms are highly variable from year to year, with some individual mega-events claiming tens of thousands of lives, when in other years, the global total may be between 10 and 20 thousand lives lost.

From the late 20th century to the early 21st century, significant advances in short term weather prediction have dramatically increased the skill with which many severe storms (and storm specific impacts) can be predicted, saving many lives. This is true not only in affluent countries with very high resolution data (eg. US and Europe), but it is also true of some much poorer countries. In 2019 and 2020, there were several cyclones that hit northeast India and Bangladesh that were every bit as powerful and intense as a devastating cyclone that struck in 1970 and killed hundreds of thousands of people…however, the death toll was dramatically lower in the more recent episodes because of the forecasting capabilities, forecast dissemination and government response of the Indian and Bangladeshi governments. However, there are of course, some notable depressing exceptions in recent years of natural disasters in relatively affluent countries that had a devastating human toll…many of the deaths and disarray and infrastructural collapse that accompanied Hurricane Katrina in the US in 2005 and Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico in 2017 were a function of an inept, dysfunctional government response – scientifically, both storms were relatively well forecast.

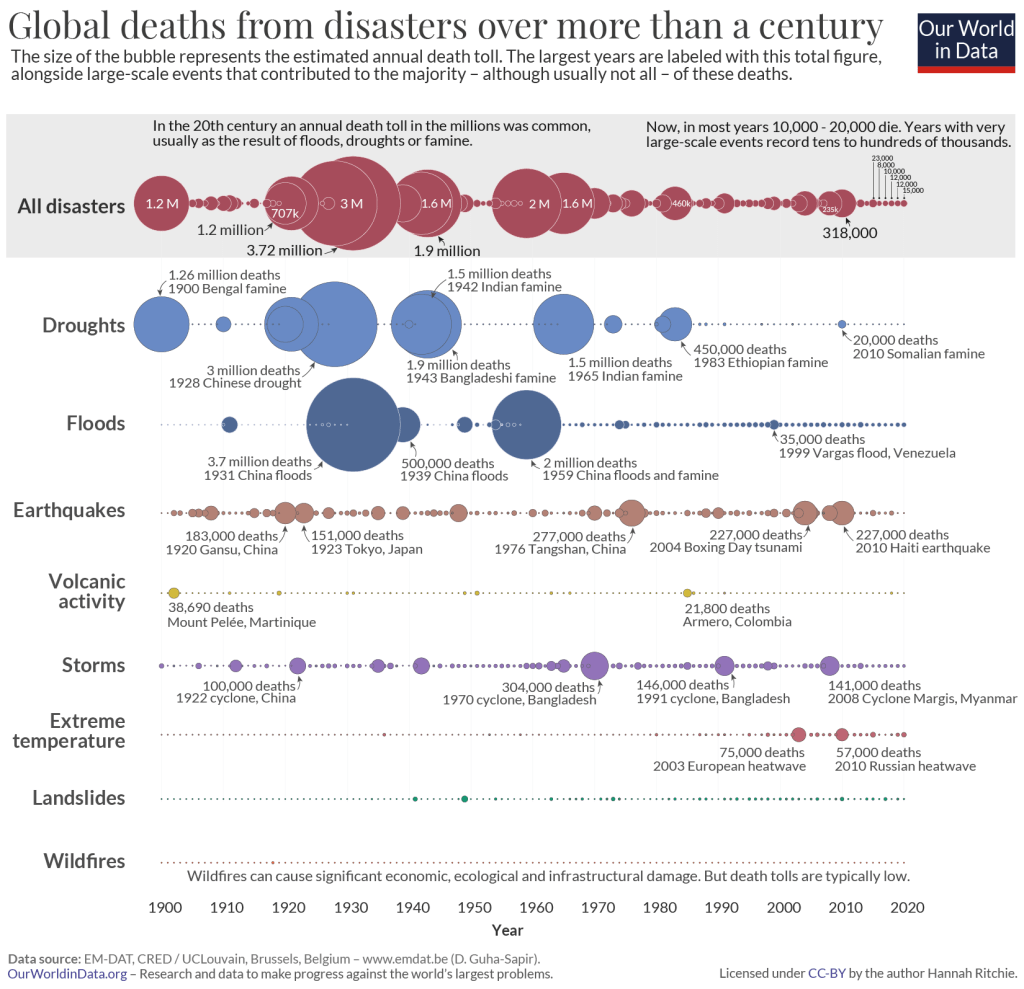

But all in all, globally, the average number of lives lost per storm in severe storms has had a tendency to decline over the long run. The diagram below shows the number of casualties from all natural disasters from the last century.

source: https://ourworldindata.org/century-disaster-deaths

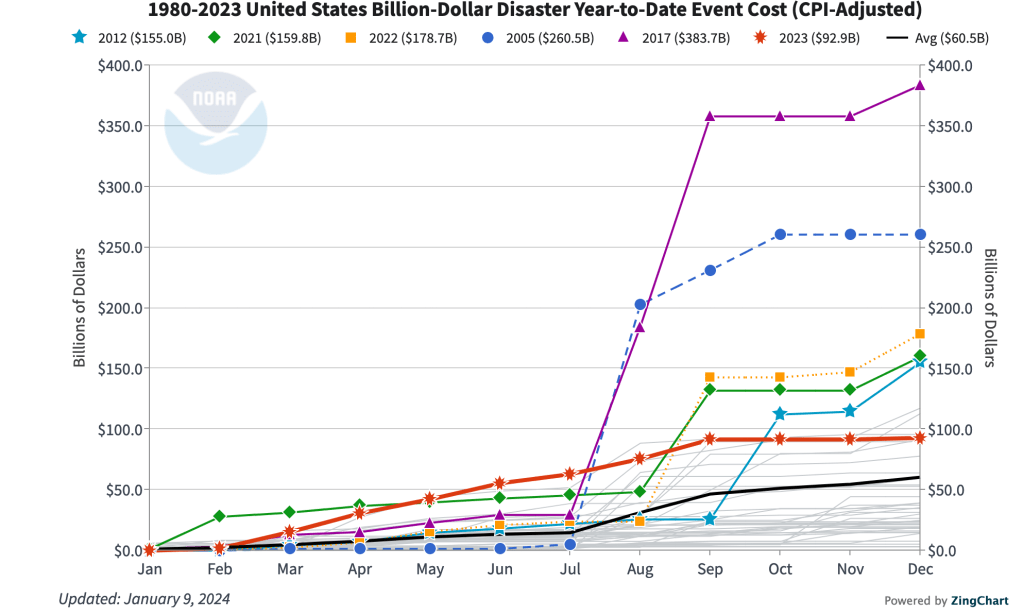

However, as severe storms are getting more severe, may be getting more numerous and as more people are living in vulnerable areas, the total economic value at risk has been steadily increasing – so the frequency and total losses of billion dollar meteorological disasters has been steadily rising. The figure below shows the costs of billion+dollar disasters in the US from 1980 to 2023.

source: https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/billions/

Beyond those direct impacts, severe storms can harm critical infrastructure like energy, water and public health systems, imperiling populations who are at risk or already hospitalized. Severe storms can also cause added risk of exposure to toxic substances in stormwater or harmful mold as floodwaters recede. Sometimes, the extent of stormwater damage on a structure may not become fully apparent until sometime after the stormwater recedes. Severe storms can also damage and undermine water treatment capabilities and in many water management systems, stormwater combines with wastewater and can lead to outbreaks of water borne diseases like cholera.

Other indirect impacts of severe storms include impacts on mental health and economic well-being. Even if a person and his/her immediate family survive a severe storm and are not badly injured or sickened, a storm that devastates a community, cuts off critical resources and services for an extended time and causes significant property damage can be a major trigger for depression and economic challenges in the aftermath. A diagram of the interwoven connections between hurricane risk and health impacts is shown below from a recent paper.

source: Lee et al. 2021, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health

Systemic Climate Changes (vector borne diseases)

Systemic climate changes (persistently warmer temperatures, rising sea levels and changes in precipitation) also tend to have lasting impacts on the ecology of disease vectors and can change the epidemic risk of certain diseases, including malaria, dengue, zika, chikungunya, Rift Valley Fever, Lyme disease, and West Nile Virus. This has been widely documented in the peer reviewed literature and the United States Global Climate Research Program (USGCRP) has published a report to this effect for vector borne diseases in the US (USGCRP report). In most cases, both the pathogen (bacteria, virus or amoeba) and the vector (mosquitos and sometimes other animals) have an optimal temperature and precipitation range in which they grow more rapidly and reproduce more rapidly – causing greater likelihood and frequency of human infection. Often these conditions are favored when temperatures are high and precipitation is high – although the dynamics can be a bit more complex.

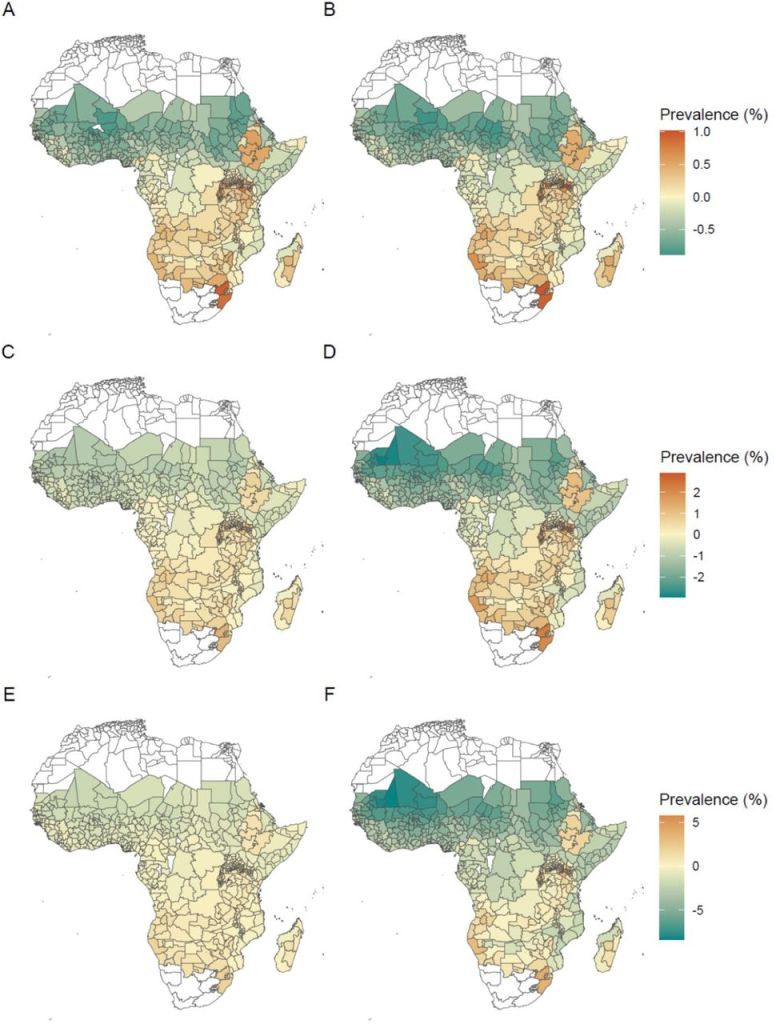

Globally, of all the vector borne infectious diseases, malaria is the most deadly. While widespread mosquito spraying campaigns have largely eliminated the risk of malaria transmission in places like the US and Europe, and there is now a recently developed vaccine against malaria that may help to significantly reduce risk, over 200 million people are infected with malaria annually and in a typical year over half a million die from the disease (mostly young children in very poor settings – particularly in Africa). As temperatures rise and precipitation patterns change, the areas suitable for malaria transmission and mosquito breeding evolve and may increase. The figure below shows modeled changes in malaria prevalence in Africa in the mid and late 21st centuries on the basis of three climate change scenario story lines. Subfigures A C and E show the modeled malaria prevalence around 2050 and B, D and F show the modeled malaria prevalence around 2100. The top two maps (A and B) are for the low emissions scenario (RCP 2.6), the middle two (C and D) are for the intermediate emissions scenario (RCP 4.5) and the bottom two (E and F) are for the high emissions scenario (RCP 8.5). Note the scale changes for the different emissions scenarios.

source: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2023.07.16.23292713v2.full

Another class of vector borne diseases in global tropics are the arboviruses (dengue, zika and yellow fevers). The aedes aegypti mosquito is the primary vector for these arboviruses. There are many infections with these diseases per year (particularly dengue fever – which can have as many as 400 million infections per year), but fewer deaths than with malaria (under 100,000 between all three combined). They nevertheless pose a serious health hazard to affected individuals and can lower the quality of life and add new risks even to those who recover from the disease.

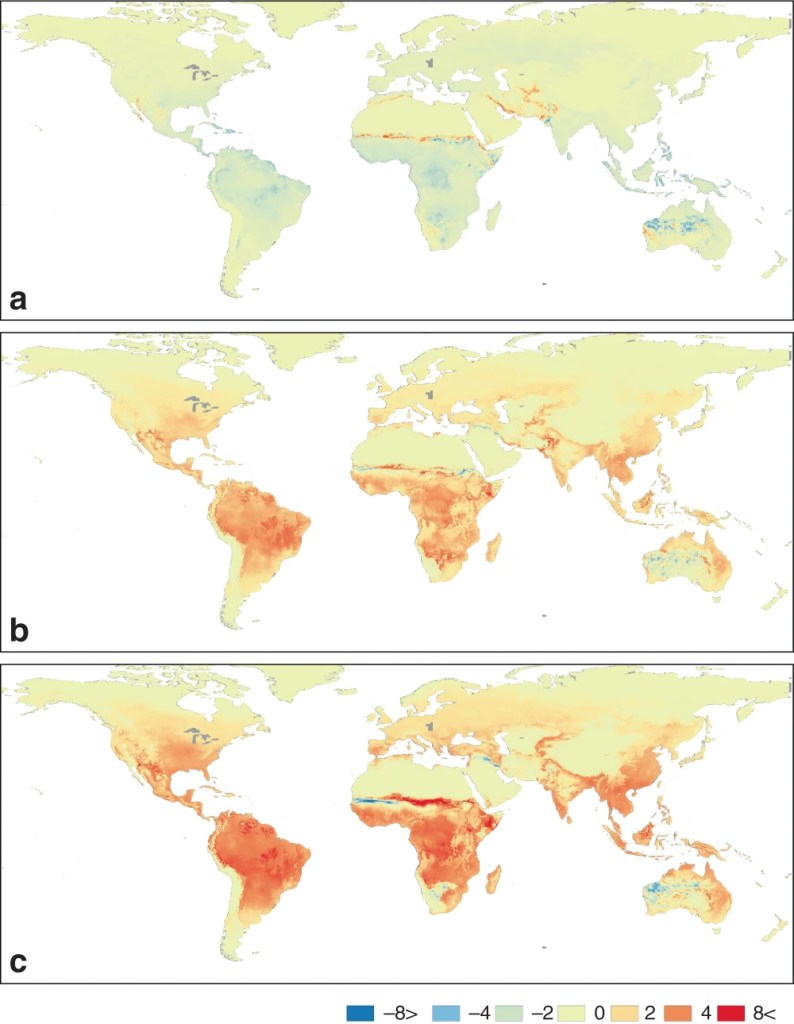

source: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-020-16010-4/figures/2 – Iwamura et al. 2020, Nature

The figure above shows the changes in life cycle completions (or LCC) for the Aedes aegypti mosquito (vector responsible for dengue, zika and yellow fever). The top panel is the observed number of life cycle completions in the 2000s minus the average in the 1950s. The middle panel is for the modeled LCC in the 2050s (using RCP 4.5 – middle of the road emissions scenario) minus the observations in the 1950s. The bottom panel conveys the same information as the middle panel, but using RCP 8.5 (high emissions scenario). Again, we see a trend that a warming planet is likely to be favorable for the wider spread of these disease vectors. The IRI has also developed maprooms for AEDES and malaria risks.

Systemic Climate Changes (allergens)

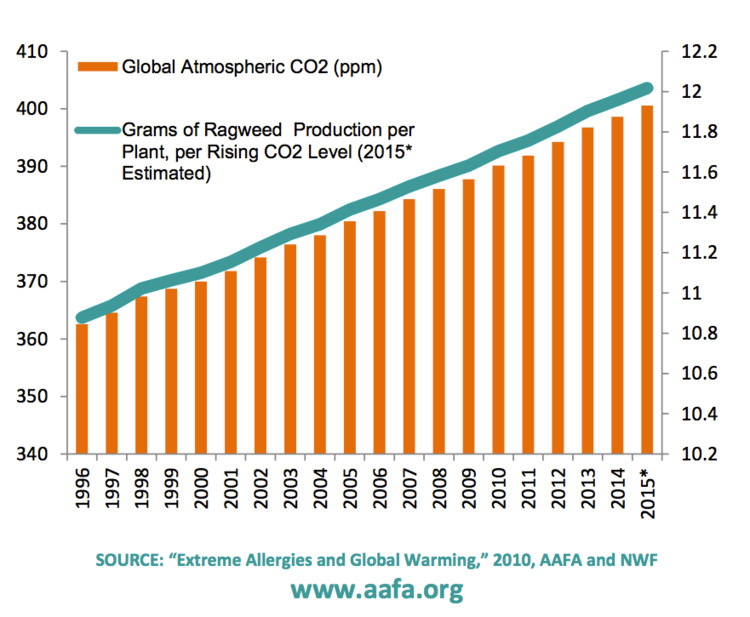

Systemic climate changes and changes in atmospheric carbon dioxide also tend to produce conditions favorable for the intensification of aero-allergens. Warmer conditions year round tend to lead to longer pollen seasons and higher pollen counts in the air for many allergens. The graph below shows the trend of ragweed concentration and the global CO2 concentration.

Source: https://aafa.org/ (Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America)

Some of the connections between climate change and allergens are further explored in a report by the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America (AAFA report) in 2010.

Systemic Climate Changes (food security, displacement and conflict)

While these topics are discussed in greater detail in the pages on security, biodiversity loss and agriculture/food security, our changing climate also leads to systemic environmental degradation which affects food production, biodiversity and can also lead to forced migration and civil conflict – which clearly have many other physical and mental health impacts.

source: https://www.loe.org/shows/segments.html?programID=22-P13-00011&segmentID=2

One of the important organizations trying to address this issue of forced migration in a humane and respectful way is https://www.climate-refugees.org/.